Photo by Picsea on Unsplash

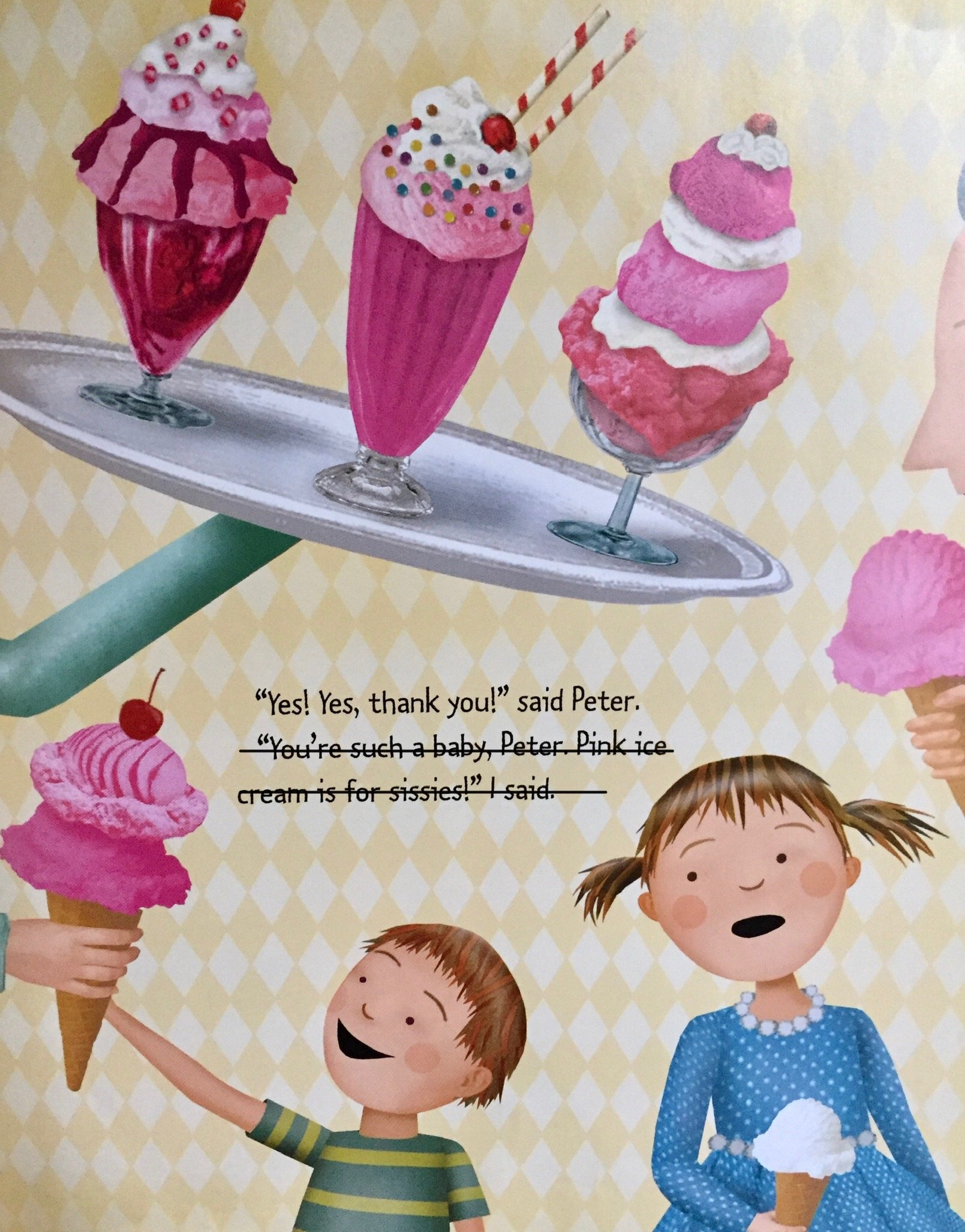

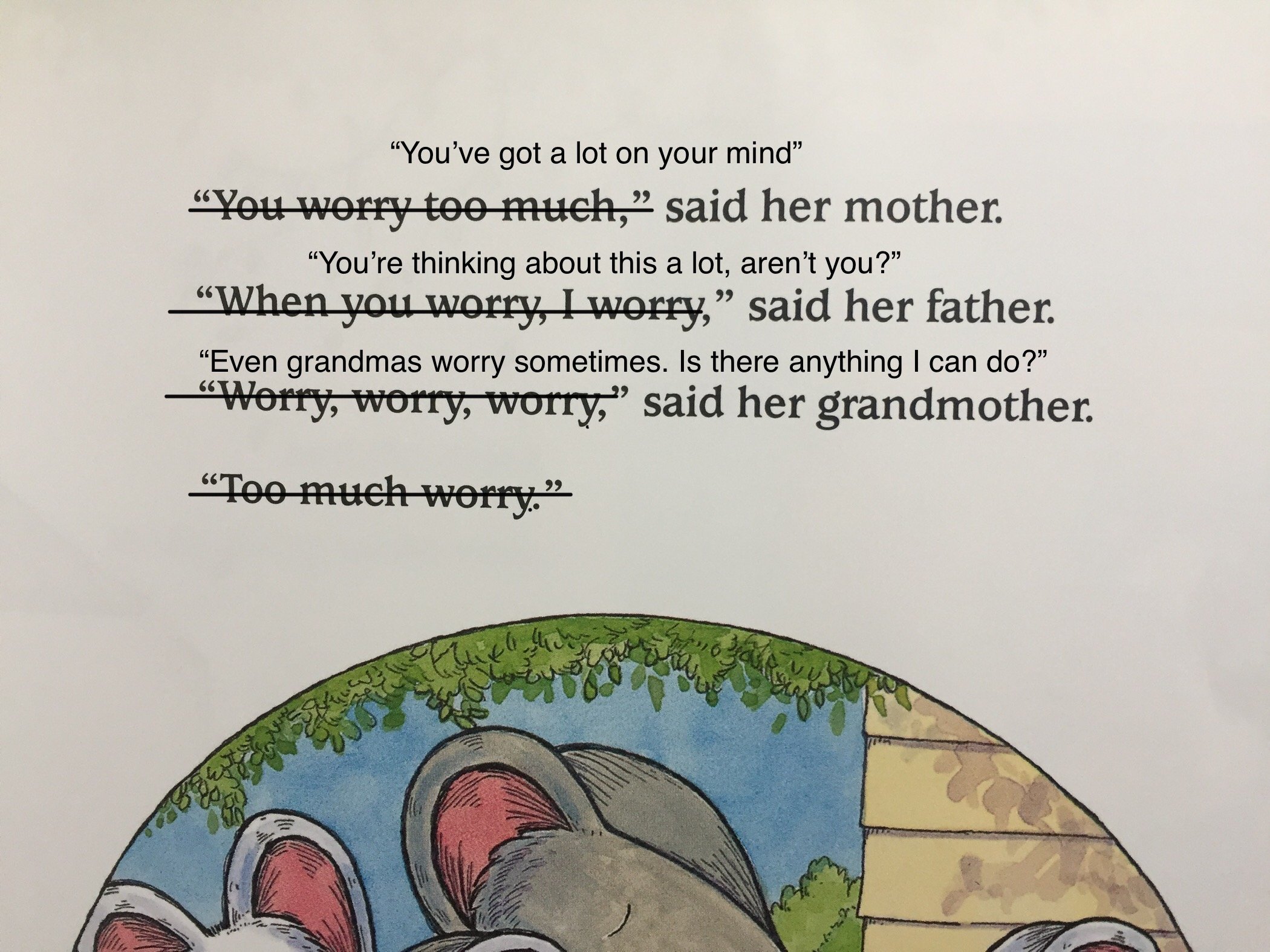

As time goes by and I become clearer and more intentional about the language I use when speaking with young children, I often encounter passages in children’s books that don’t quite align with the messages I’m striving to communicate. Particularly if you’re fond of older children’s literature (but nonetheless still very present in modern books) you may often encounter examples of racist, sexist, and ableist stereotypes, outdated and culturally insensitive references, unnecessary name calling or teasing, and the blatant, if perhaps well meaning, minimization of children’s emotions and experiences. What’s a thoughtful caregiver to do?

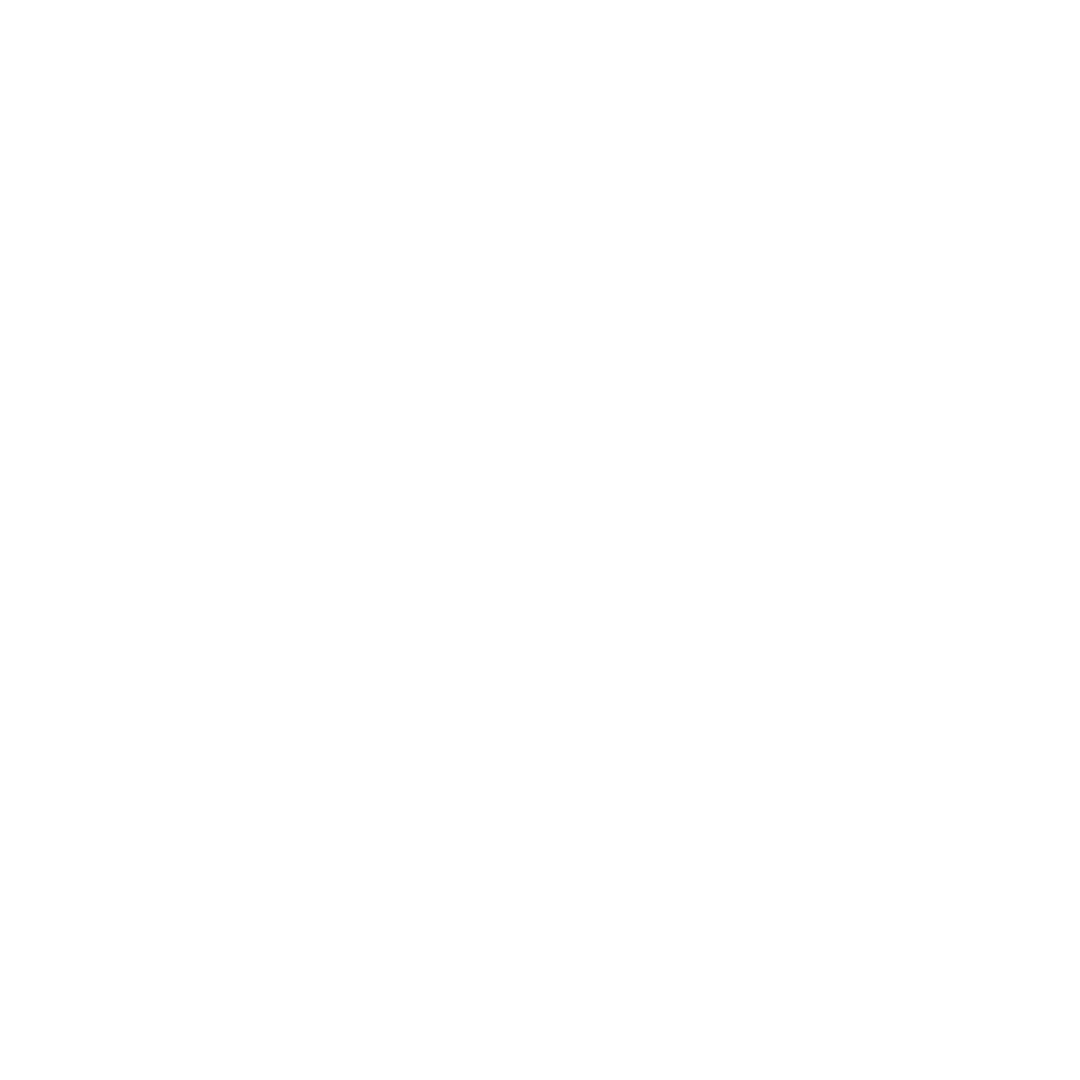

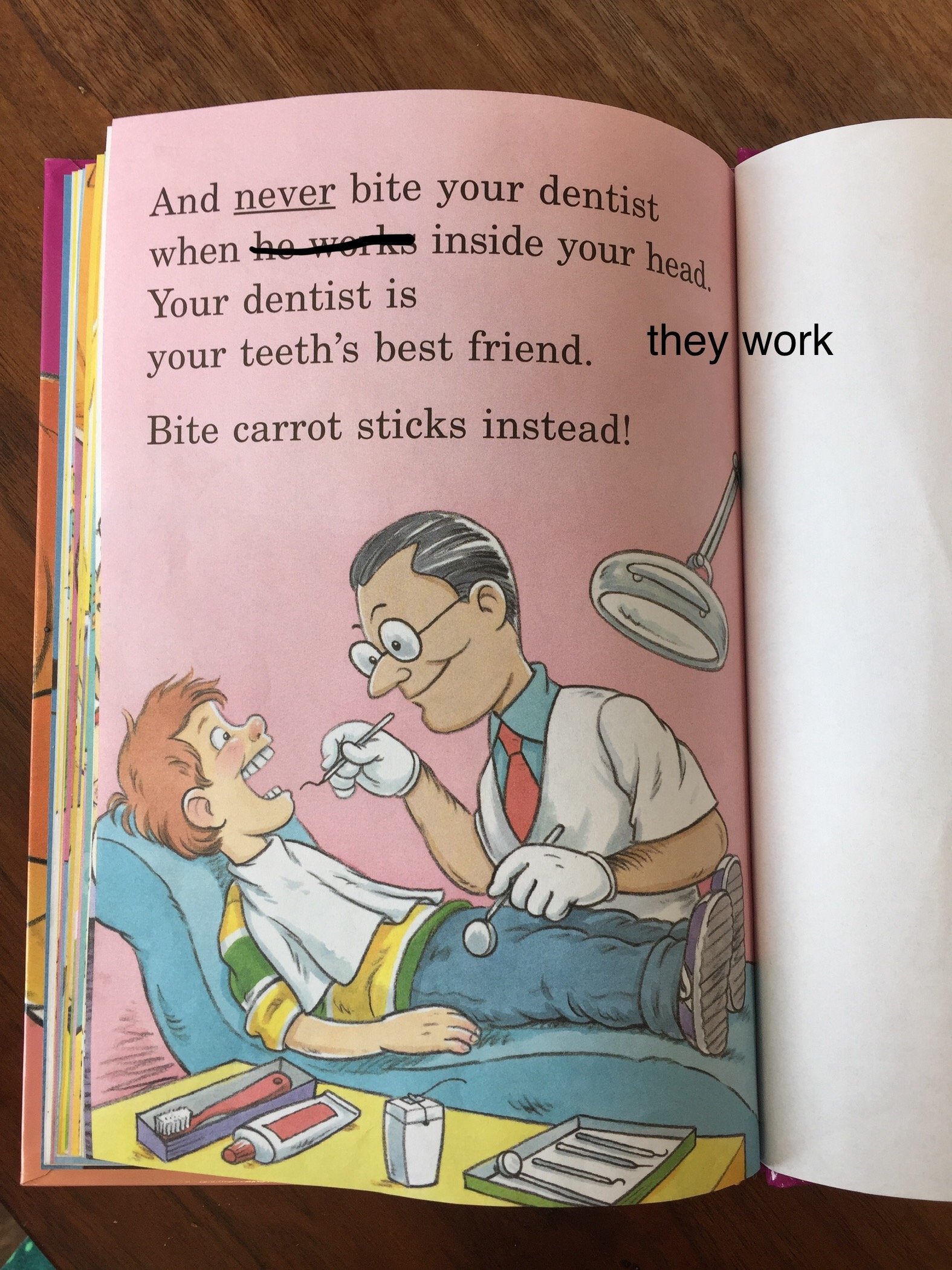

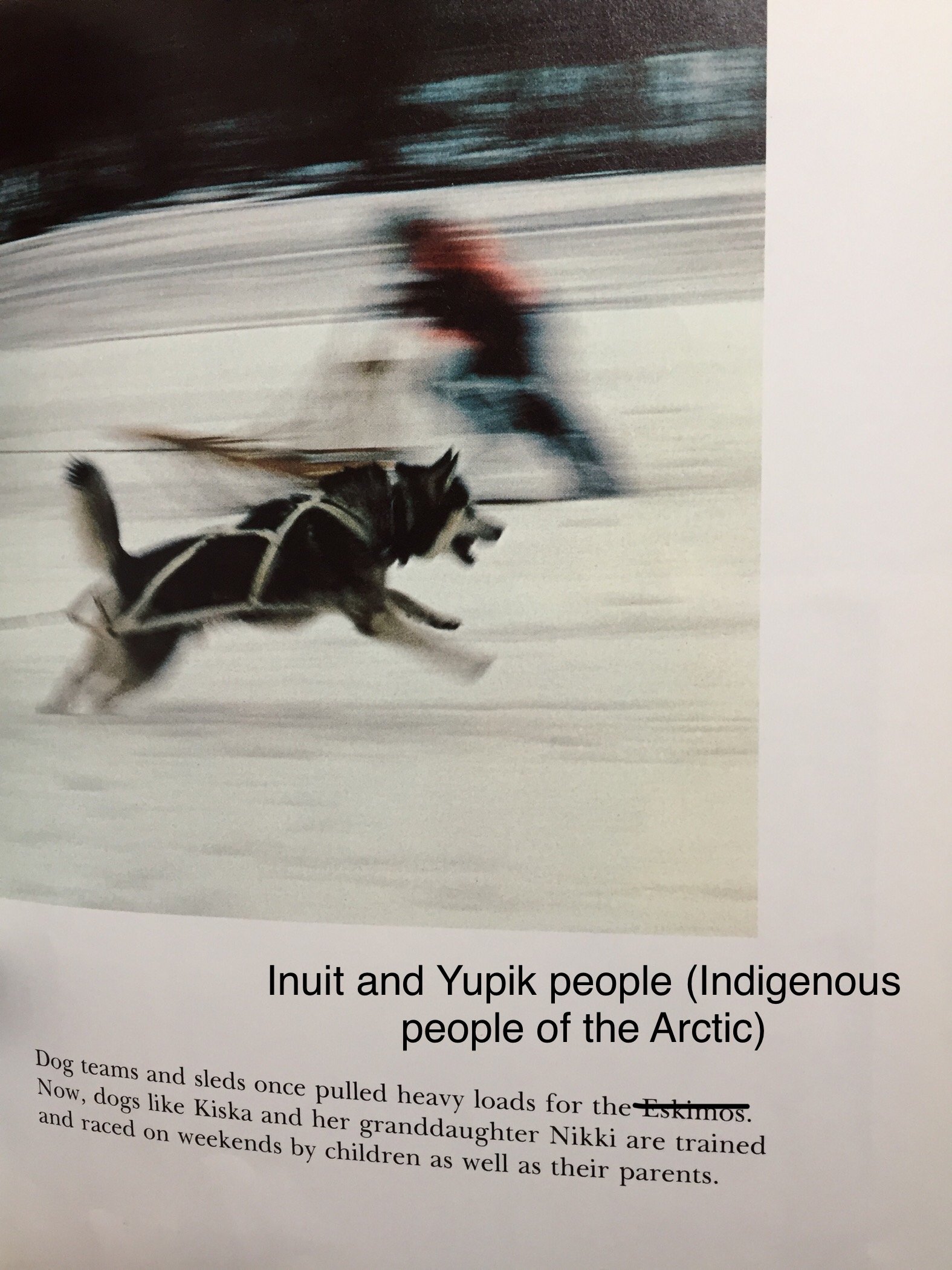

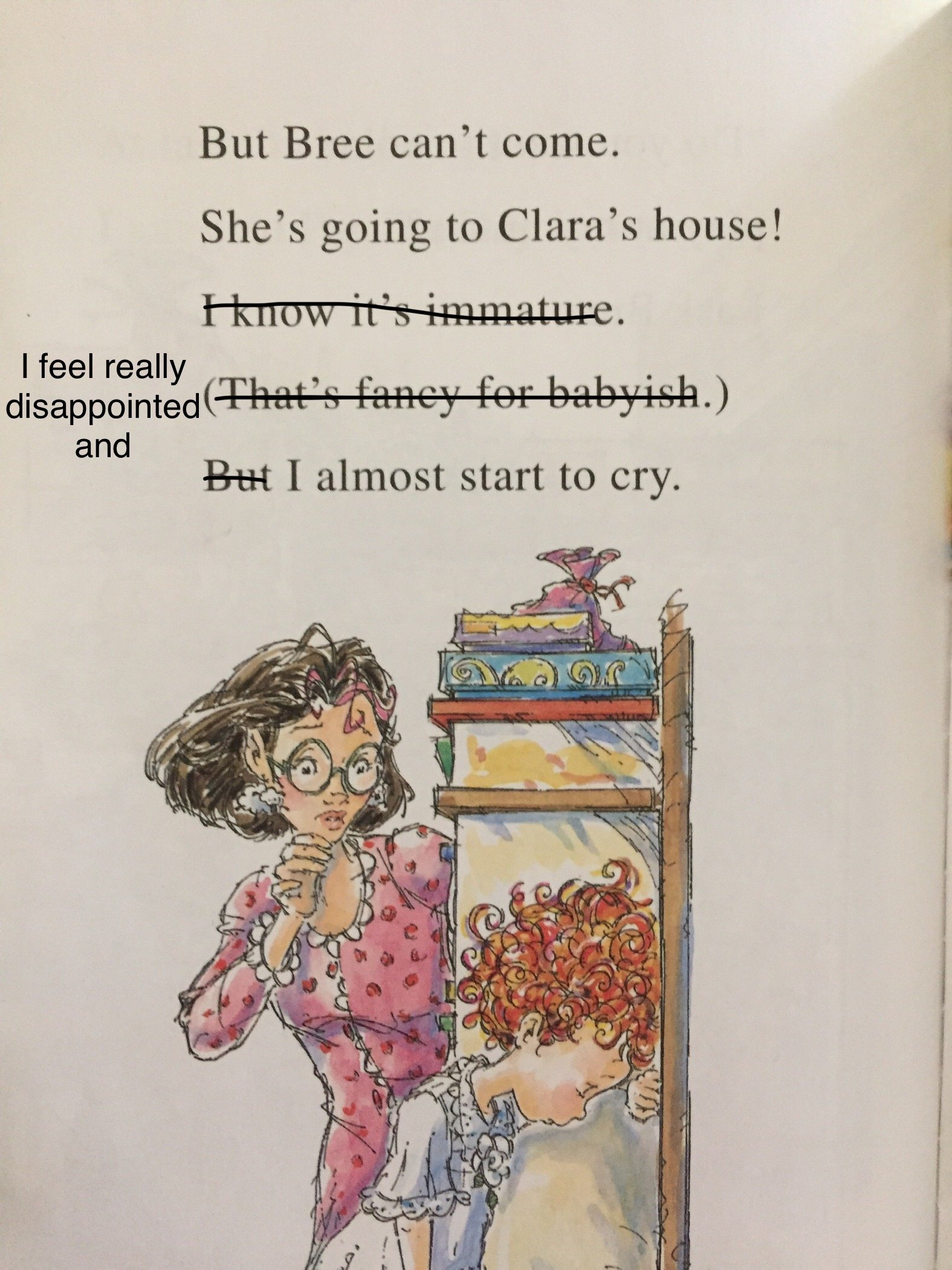

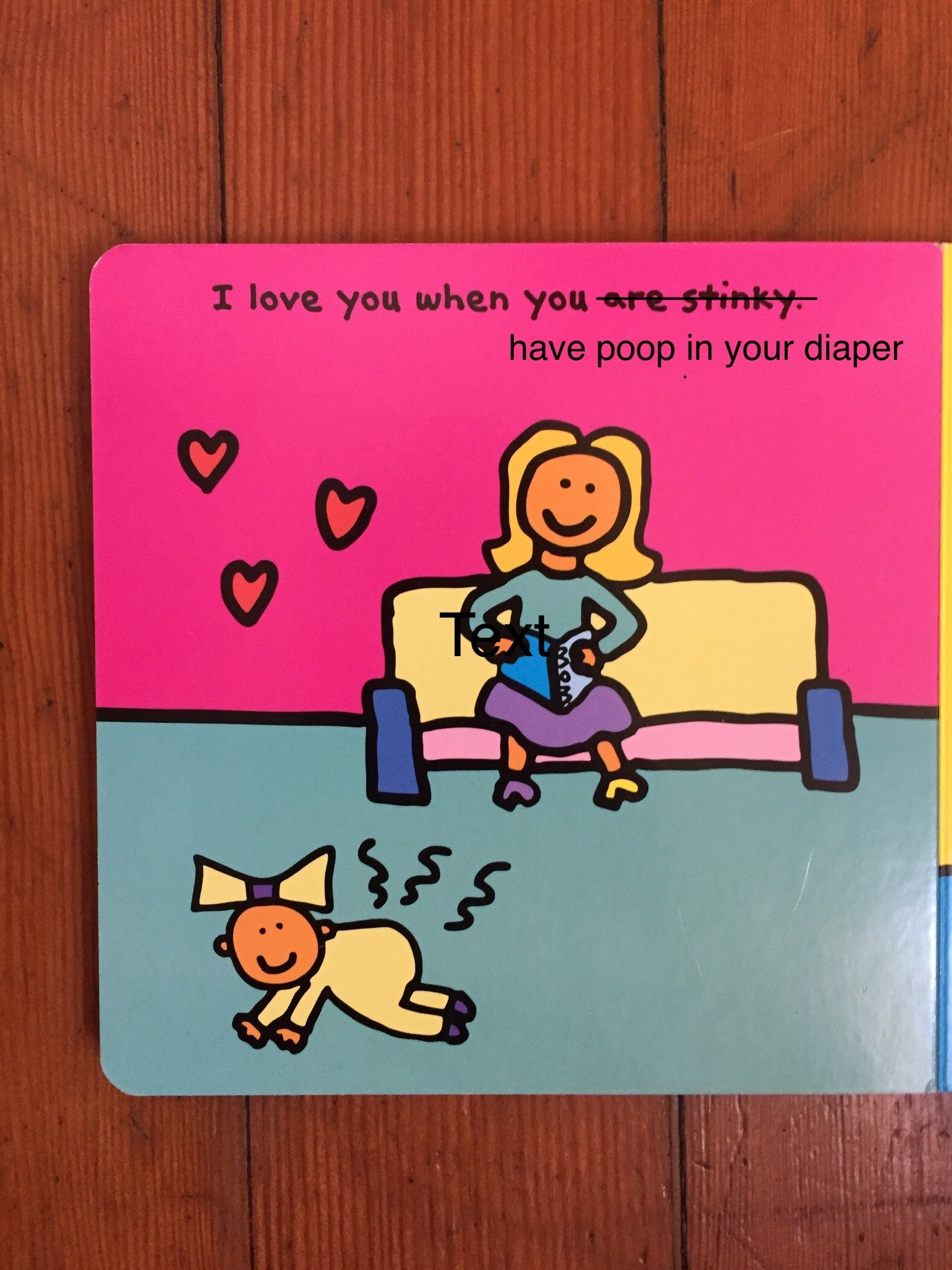

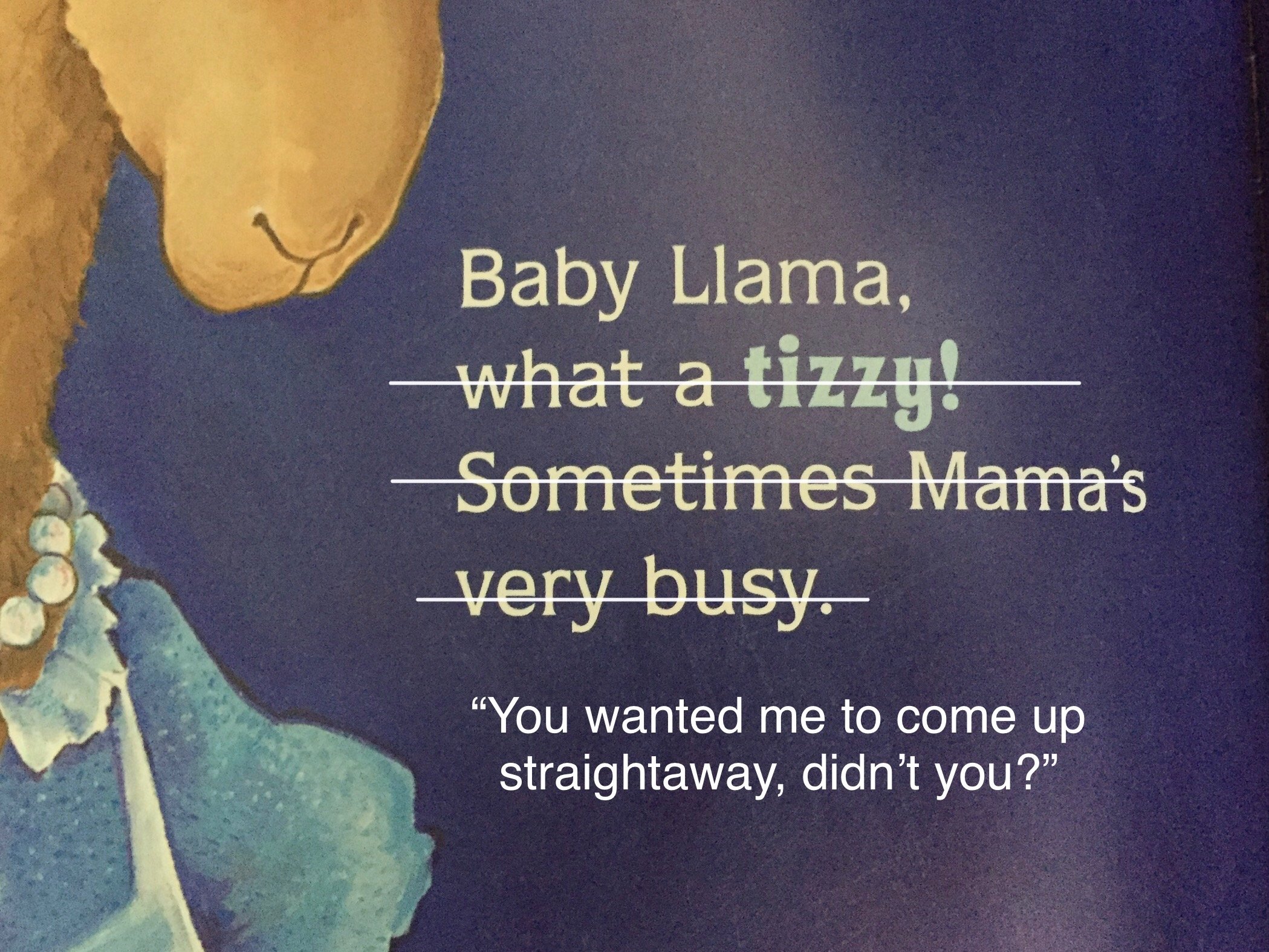

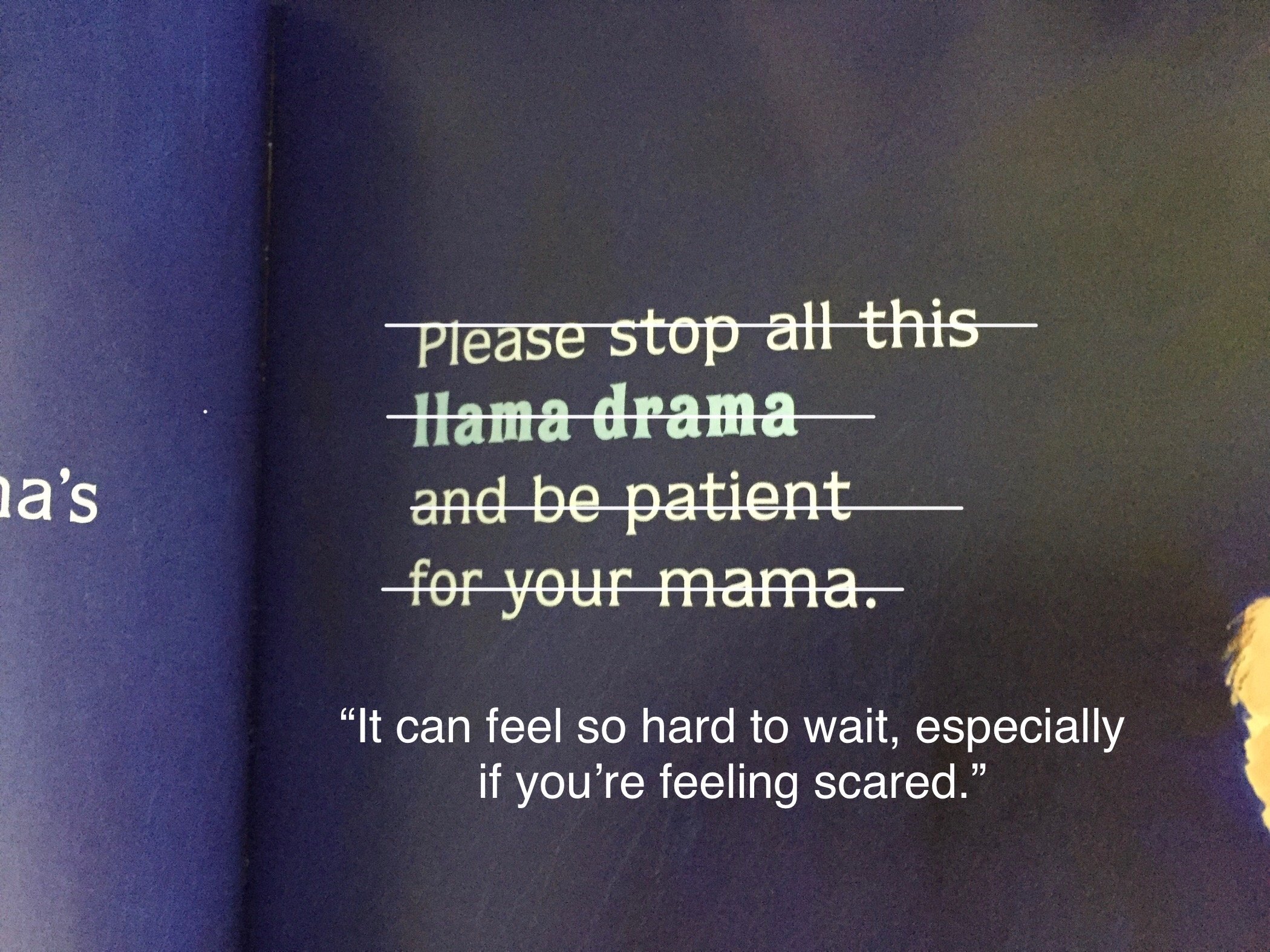

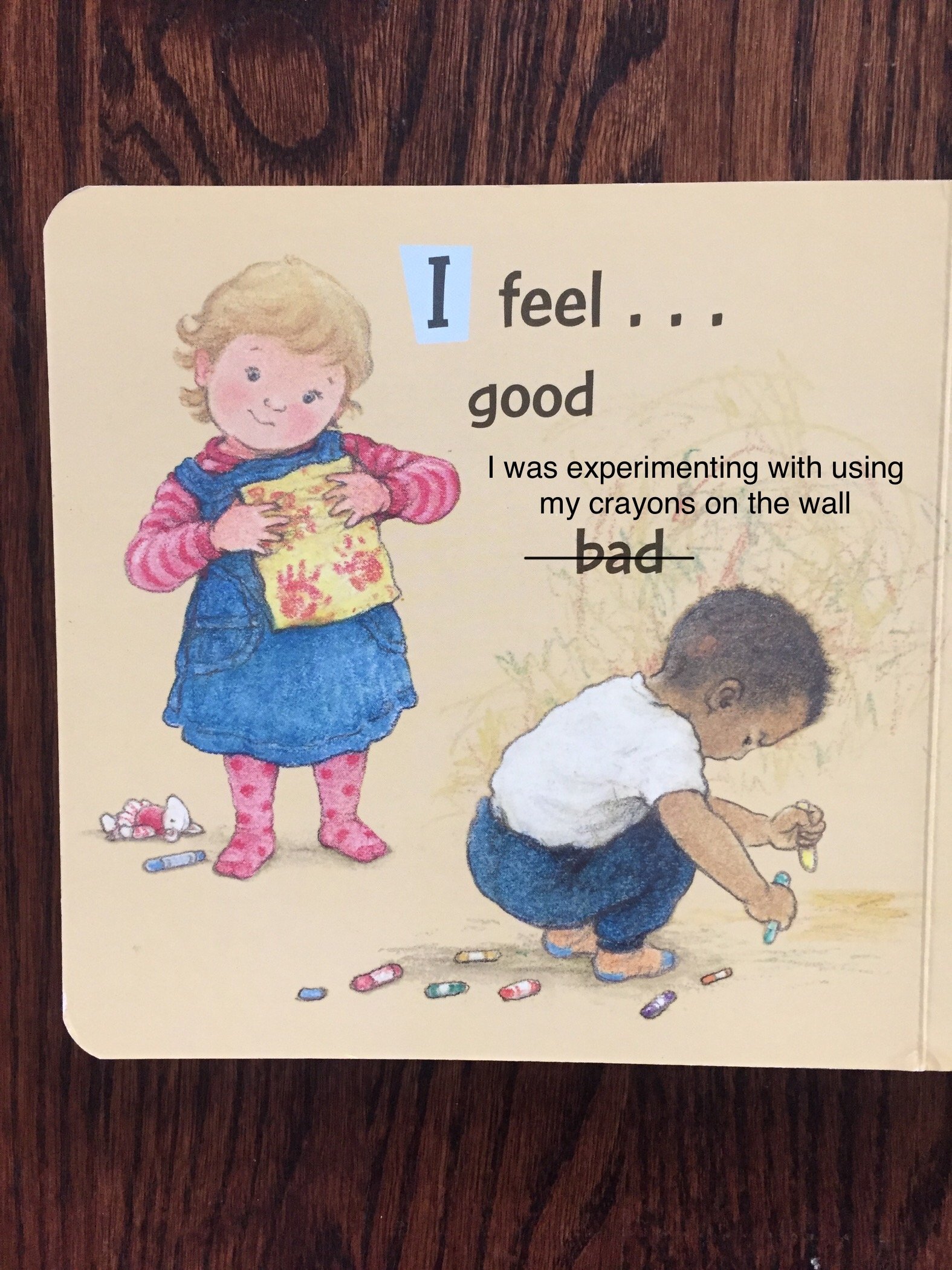

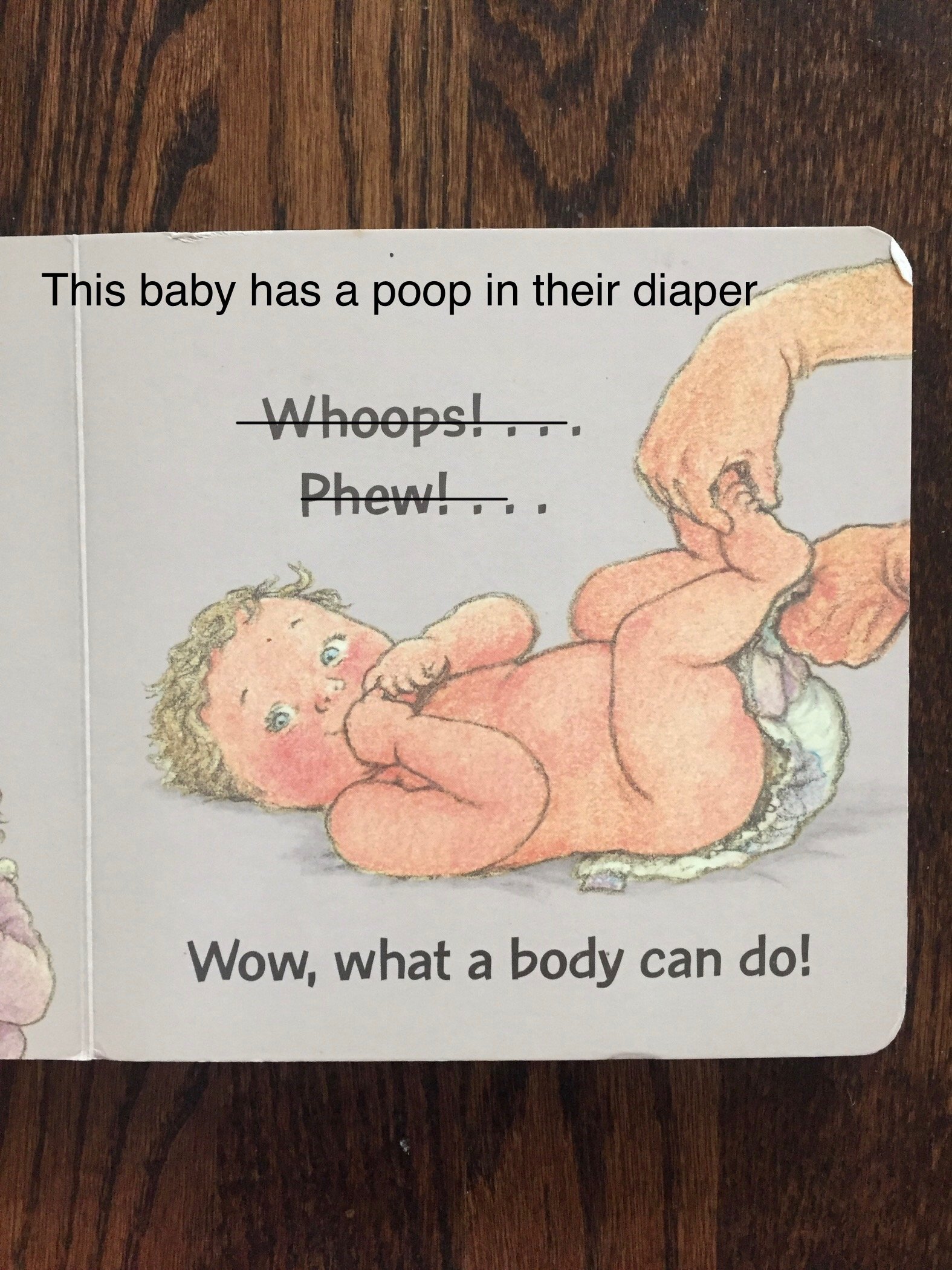

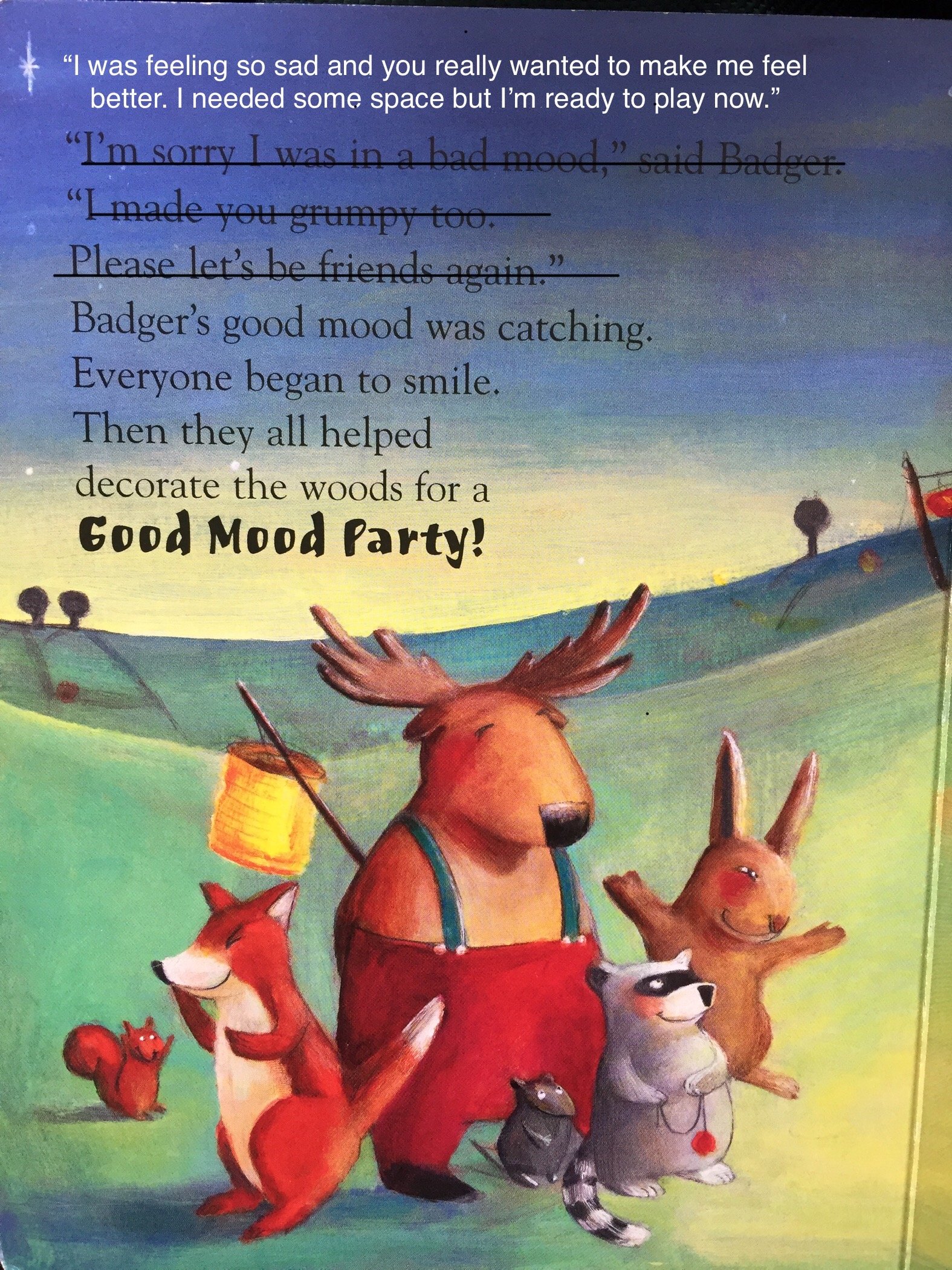

When we recognize that the literature may possess other value (an intriguing plot, delightful illustrations, a certain je ne sai quoi that draws children, perhaps inexplicably) but we find issue with certain passages, we can employ the practice of radical editing. This was first modeled to me by my fellow educators at a local preschool where I once worked. As a person who rarely--by choice--flies by the seat of my pants, I was impressed by their ability to make mindful and creative corrections on the spot which were congruent with the respectful approach we were all striving for.

Radical editing can be done in the moment, or by inscribing new words on the page itself-- infusing the books with more thoughtful and prosocial language. The benefit of the latter is that (aside from having time to consider how you’d prefer the passage to read) all of the adults reading to the child(ren) will be communicating a unified message. A good rule of thumb: if you wouldn’t say it to your child, don’t read it aloud. While we recognize that we can’t insulate children from the realities of the world (e.g. prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination or insensitive and unkind communication styles), we can ensure that the messages children hear coming from our mouths align with our values.

As children age and their brains mature, they become better equipped to hold multiple perspectives--to understand that other people do things differently and say things differently than what they’re accustomed to in their family. They can more readily reconcile the discrepancies between what’s being read to them and what we, their parents and caregivers, actually believe. Ideally they will have had enough validation at this point--years of respectful, reciprocal communication to serve as a solid foundation for examining literary interactions which may trigger a red flag within them. With time they will come to understand the way authors sometimes use disconcerting words (that may come across as teasing, shaming, or invalidation) intentionally* in order to communicate a point, build a character, complete a rhyme and/or stir emotions within a reader.

[*Although I cannot always give the author the benefit of the doubt that they are indeed being intentional with their use of such language. More often than not I presume it is outside of their awareness. Cheri Huber, a prolific author and (highly accessible) teacher of Zen Buddhism explains:

“The process of self-hate is so much a part of the average person that we don’t even recognize it… If you want to know what you were conditioned to believe as a child, look at the self-criticism that goes through your head now… ‘That was a dumb thing to do. Won’t I ever learn? I shouldn’t feel like this. I should know better.’

Does that mean someone consciously, deliberately treated you that way? Perhaps not. But you got the message anyway, didn’t you?”

-Cheri Huber, There is Nothing Wrong with You]

However, until children are old enough to make these distinctions, I imagine it can be quite confusing and unsettling for them to hear such words come out of our mouths, even if they can sense that they aren’t being directed towards them.

Every time you sit with a child and read a book, remember that it is an opportunity--a valuable, relationship-affirming opportunity--for connection, for learning and to nourish curiosity, wonder, imagination and the joy of the written word. You are not only helping lay the foundation for language and literacy development as well as social-emotional intelligence but, through the words you read to your child, you are communicating the kind of world your child can expect to find outside the walls of your home and what kind of people inhabit that world. It’s up to you. Your words matter.

Sidenote: The only value I see in reading these books as they are (to older children) is that they can serve as natural and important springboards into conversations about complicated topics within the relaxed environment of your home.

Resources:

Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books by Louise Derman-Sparks https://socialjusticebooks.org/guide-for-selecting-anti-bias-childrens-books/