(6 min. read) Go to any rock climbing gym and you’ll probably be required to watch a video that shows you how to “spot” a climber (usually someone who is bouldering/climbing without a rope). In order to spot someone who is climbing, you provide your undivided, laser-focused attention, stand below or near the climber with your arms raised, ready to guide them to fall in a safe way (avoiding harm to their head or spine), but not with the intention of preventing a fall, and support them with words of encouragement and the occasional technical suggestion (but only if/when the climber is asking for it).

It’s not that different for children. Of course, sometimes (if we’re able and the consequences would be high) we will catch them. But it’s not always possible or (gasp) advisable. I remember being in a toddler swim class where the instructor reminded us to allow the child to dip under water briefly if they jump in to the pool–we really want them to begin to learn about what it means to be in water and how their actions have consequences. If they magically float every time they’re in water (because we stop them from dipping under or because they wear floaties) they’re actually at much greater risk around water. The equivalent for this on land is learning how gravity works and how to fall.

“Learning to fall, getting up again, and moving on is the best preparation for life. ”

It’s helpful to hold in mind the goals of physical activity and exploration for children:

for children to learn their limits so they can keep themselves safe (because one day we won’t be around to keep them safe)

for children to practice making decisions & discovering the outcomes of their actions

for children to maintain the experience of movement as being joyful, self-directed, and a way to pursue mastery

for children to develop confidence, strength, balance, and coordination

In a podcast I recently listened to about safety in the (Montessori) home, parent educator and mom, Nicole Kavanaugh voiced what she knew might be a controversial opinion. She remarked,

“I want them to bump their heads when they’re little because it’s going to teach them where… things are and where their body is in time and space because it’s a heck of a lot easier for them to learn it then than to spend a lot of time learning it when they’re older and the consequences are a lot higher.”

Yep.

Before we get into the how-to of spotting a climber I want to first address a few of the reasons why climbing can be so difficult to watch.

It can be incredibly anxiety provoking. Our minds go down the rabbit hole of fear and fortune telling (which can easily and quickly become quite grim). If we don’t have a good handle on regulating our own anxiety or challenging our own cognitive distortions and fear stories our anxiety will impact our child’s confidence and perception of what kind of a place the world is and their ability (or lack thereof) to navigate it safely. Hovering and offering unhelpful statements (BE CAREFUL!) are ineffective strategies we use to quell our anxiety that can actually interfere with our child’s ability to keep themself safe.

“Adult warnings to “be careful” are redundant at best and, at worst, become focal points for rebellion (which, in turn, can lead to truly risky behavior) or a sense that the world is full of unperceived dangers that only the all-knowing adults can see (which, in turn, can lead to the sort of unspecified anxiety we see so much of these days). Every time we say “be careful” we express, quite clearly, our lack of faith in our children’s judgment, which too often becomes the foundation of self-doubt. ”

I vividly remember a story Dr. Lawrence Cohen tells in his book, The Opposite of Worry. He’s at the park with a friend and his 3-year-old daughter. She’s climbing and he’s fretting over her, reminding her to be careful, and wringing his hands with anxiety when his friend suggests, “She’ll recover better from a broken arm than from being timid and unsure of herself.” Wow. Of course, she didn’t break her arm that day but this story reminds us that taking time to notice exactly what we might be communicating when we hover or project our own fears onto our climbing child is an invaluable awareness that will serve us throughout our child’s life.

We can set ourselves up for additional anxiety by helping our child into or onto places they can’t access through their own strength or ability.

Avoiding the temptation to place your child into spots (slides, play structures, etc.) they can’t safely access on their own goes a long way towards keeping your child safe. Young children are realistically limited by height, strength, and capacity to be able to get themselves into very unsafe places (for the most part). There’s a reason the first step to a play structure is usually taller if it isn’t made for toddlers. This is not to say that they won’t ask, especially if they’ve become accustomed to you placing them in higher up spots!

I remember when one of the children I used to care for was a young toddler she really wanted me to place her onto a spring rocker at the park but I wouldn’t because I didn’t think it was safe (and because it’s a crucial tenet of Magda Gerber’s Educaring® approach). I would validate her frustrations, “You really want me to put you up there, I hear that. I don’t put kids into spots they can’t reach on their own. You can try to figure out a way to get up there.” I would also remind her that someday she would be able to reach. It was tricky to wait but voila! Eventually the day came where she was able to reach and it was VERY exciting. Her wide smile and excitement—once she was able to climb up all on her own—was priceless.

We might not know the difference between risk and hazard.

When we educate ourselves on the differences between risks and hazards (and dive into the benefits of so-called risky play, or safety play as “Teacher Tom” Hobson calls it) we can be better equipped to support our child’s exploration.

“Play scholars and activists define a hazard as a danger in the environment that could seriously injure or endanger a child and is beyond the child’s capacity to recognize. Risk is then defined as the challenges and uncertainties within the environment that a child can recognize and learn to manage by choosing to encounter them while determining their own limits.” (“Risk, Hazard, and Play: What are Risks and Hazards?”)

“We do come near so that the infant knows we are available, which brings about a certain amount of security… We would like to convey the feeling, “I think you can handle it, but if not, I am here.””

Ok, now that we’ve unearthed some of what can come up while observing a child climbing I want to suggest a 5 step process for selective intervention:

Observe closely from a distance.

If the consequences of falling would be severe or you feel like your child would benefit from more support (also see below for other factors), inform the child of your intention & slowly and without great concern move closer to them (“I’m going to come a little closer in case you need any help”). Sprinting over can distract them.

You may decide to bring your hands near–but not touching–your child (behind or under their back or bottom) in order to support them if they fall.

If a child appears stuck, frustrated, or overwhelmed, use words to describe what you see and acknowledge emotions; offer alternatives/ideas (“Hmmm, looks like you’re wondering how to get down the Pikler triangle. Could you step one leg down here?” and point to a lower rung).

If you’ve attempted step 4 and a child still seems frozen they may need some physical support (“I can help you. I’ll lift you down.”).

And finally, acknowledge that learning to tolerate the discomfort of allowing your child to take small, developmentally appropriate risks is a journey without a destination. You may never feel completely at ease when your child is climbing, or running at top speed, or scootering lickety-split (I certainly don’t and I’ve logged many thousands of hours caring for children and being singlehandedly responsible for their safety) and that’s okay. Many folks experience complex feelings about their kiddos growing up and becoming more independent and that’s okay too. A blissed out, lying on the beach, sipping out of a coconut type calm isn’t what we’re after in these moments. However, a growing awareness of the thoughts and stories that come up in conjunction with a broader repertoire of self-soothing skills is what we can move towards. Hip, hip, hooray for climbing!

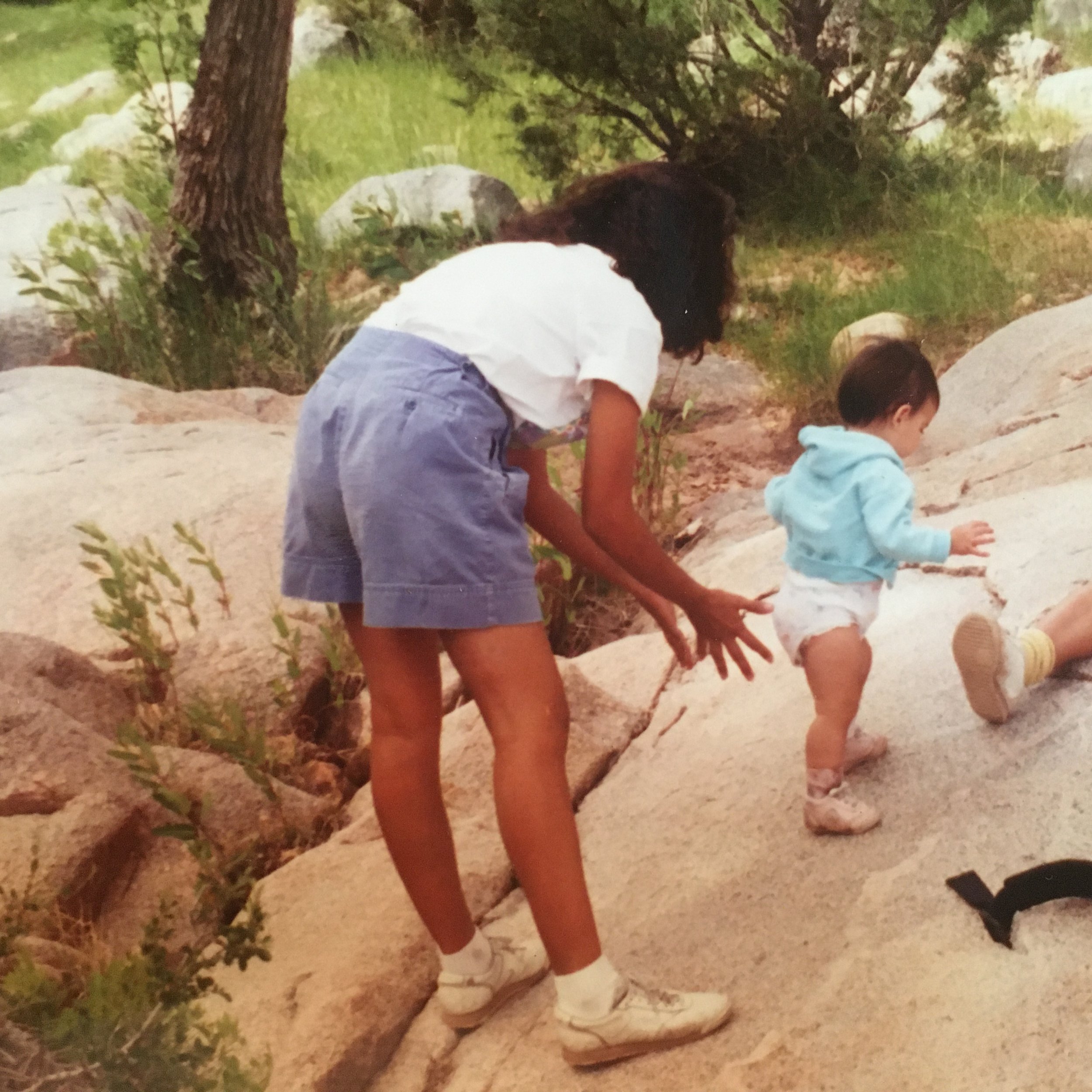

[Photo note: At the beginning of this post you’ll see my mom spotting my sister on a rather steep boulder. I love these photos so much because you can see trust, patience, and a calm allowing of developmentally appropriate exploration in action.]

[Note: If you find that your anxiety is interfering with your ability to tolerate your child’s developmentally appropriate exploration it might be beneficial to seek out some additional support from a qualified mental health provider.]

Resources:

Don’t Stress, Just Spot – How to Keep Kids Safe in Challenging Situations Without Taking Over by Christina Vlinder

Finding the Line Between Rescuing and Supporting Kids by Dr. Lawrence Cohen

Risk, Hazard, and Play: What are Risks and Hazards? from the Canadian Public Health Association

“Safety Play” by “Teacher Tom” Hobson