(5 minute read) I wrote this guide during election week 2024 and thought about it recently as being equally relevant during this moment when so many of us are feeling scared, overwhelmed, angry, and/or powerless about the injustice in our country (and across the world). I’ve found myself–at times–spiraling into hopelessness and getting stuck there. In those moments I forget completely about my arsenal of strategies for coping with pain and uncertainty.

A wonderful benefit from the work I do with parents is how I am continually invited (by myself) to align my behavior with my knowledge and values. I can’t share ideas for supporting sleep or regulation or authenticity or boundaries or any other aspect of well-being without being encouraged to reflect on and prioritize my own wellness. Here are a few ideas to support yourself and your kiddo(s) right now.

Honesty

Children are exquisitely attuned to our emotional states. Whether or not you are open and honest with your child, they sense your stress and worry.

My mentor, Dr. Larry Cohen, recommends being honest about our emotional states, “with the volume turned down.”

The words you use will depend on your child’s age and developmental stage. For a toddler I might say something like this:

“Can you tell I’ve been a little distracted? Some things have been happening recently in our country that are unfair and I’m feeling worried about it. Just like always I love you and I am here to keep you safe.”

Connected Rituals

Times like this will lean heavily on ritual to stay connected to yourself, your kiddo & your support network. As Dan Harris loves to remind us, “never worry alone.”

With YOURSELF this might look like:

Treating your body well (with food, hydration, joyful movement)

Meditating or sitting in stillness (even 1 minute is supportive!)

Taking 5-10 minutes during nap time to free write / “brain dump”

Finding a lovely way to treat yourself today AND savor it (it could be as simple as a special beverage or a candlelit shower)

With your CHILD this might look like:

Doing your best to focus on your child and the interaction during “wants-something” quality time [caregiving routines like diapering, feeding, bath time, etc.] and also offering yourself compassion when your mind wanders.

“Wants-nothing” quality time (observing your child at play without an agenda) may be more difficult right now. You can always pick up the practice again when you’re feeling more resourced. Alternately, slowing down to the pace of a young child and tuning in to the details can help ground you in this moment in a nourishing, joyful way (at least it does for me).

With your SUPPORT NETWORK this might look like:

Scheduling a short check in call with someone you trust and care about (naptime? this evening? tomorrow?)

Sending a voice memo or text to a loved one with whatever is top of mind

Making sure you have a therapy or coaching appointment scheduled in the next week or two

Scheduling a playdate with another family or, if you’re able, scheduling a friend-date for yourself (just knowing it’s on the schedule is reassuring)

Self-Compassion

You most likely will not be showing up right now as you normally can or would like to and for that you can offer yourself grace. You are HUMAN, not an empathy robot.

Kristin Neff’s evidence-based 3 part self-compassion break:

1. This is a moment of suffering

2. Suffering is a part of life

3. May I be kind to myself

You can use whatever words feel aligned and supportive to you.

Repeat as often as necessary.

Make a Plan for Media Consumption

Reading the news when you first wake up and/or constantly refreshing the news or social media is guaranteed to make this time more difficult than it already is. We compulsively check as a way of attempting to relieve our anxiety, even if we logically know it doesn’t work.

This might look like:

Putting your device(s) in a drawer for a period of time (I know families who have had great success with this strategy)

Deciding what frequency/duration would *actually* be supportive (noon and 3pm? for 15 minutes during nap time [set a timer or consider setting daily time limits in place for apps like Instagram]? Listening to a news podcast [e.g. The Daily] during your commute to support your desire to be informed but in a boundaried way?)

Linking your media consumption to a self care practice (e.g. meet one basic need first, stretching while you scroll, or 6 slow, deep breaths with your eyes closed)

Read good news!

Reduce Expectations

This goes along with self-compassion because, as I said before, your capacity will most likely not be what it usually is.

If there ever was a time for...

frozen pizza

take-out / fast food

“silly dinner” / Smörgåsbord

kids’ podcasts / Yoto / a lil extra screen time

letting the dishes luxuriate in the sink

postponing laundry

waiting until the end of the day to tidy toys

...it was right now

Sensing into what you need in this moment will be supportive (it might be cooking/cleaning/tidying OR it might be showing up to big feelings--both your own and your child’s; you might not be able to do both)

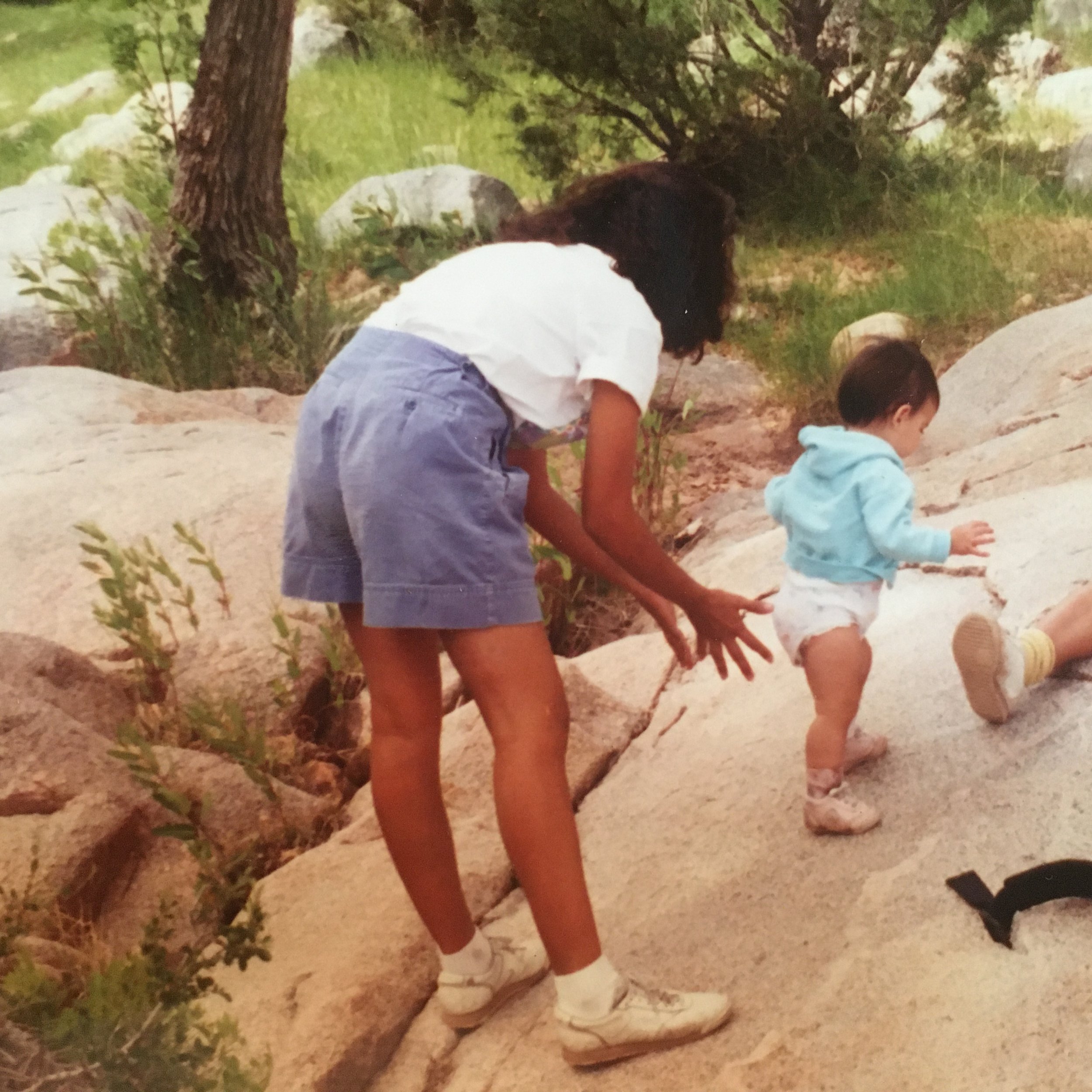

Get Outside

This might feel tricky if you’re already feeling totally exhausted but trust me, being outside will remind you of the wide, wonderful world.

It doesn’t have to be complex... city parks and neighborhood walks are accessible ways to experience the benefits of being outside.

Clinical psychologist Susan Albers, PsyD. explains the mechanism at work behind forest bathing, “The intent of forest bathing is to put people in touch with present-moment experience in a very deep way. The sights, sounds and smells of the forest take us right into that moment, so our brains stop anticipating, recalling, ruminating and worrying.”

Make Something With Your Hands

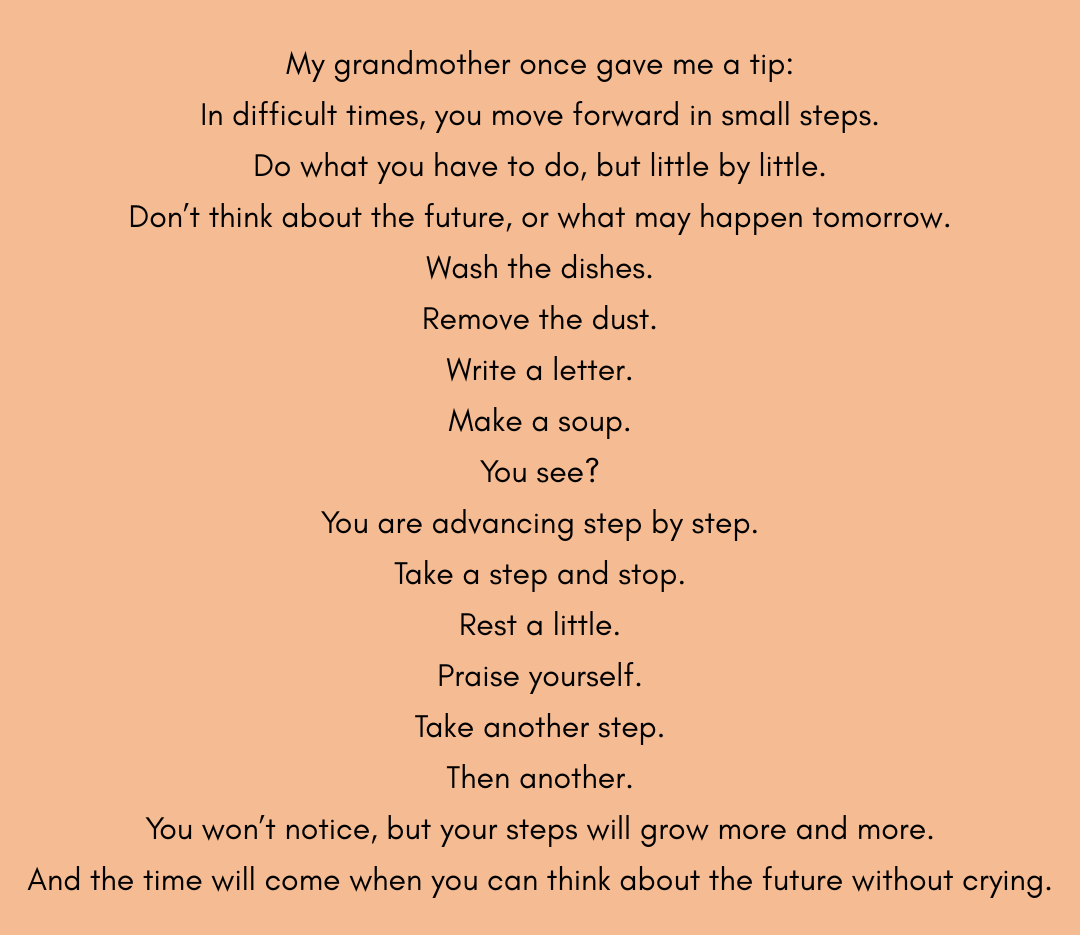

I always come back to the poem “Small Steps” by Elena Mikhalkova when things feel hard. This week I made gluten free pot pies, yogurt, and a protest banner (this is an excellent tutorial and requires no sewing).

Take Action

For me, personal values like service and social justice rise up in moments like these and I want to DO SOMETHING. I want to do LOTS of somethings. I feel overwhelmed by all of the somethings to be done. It can be difficult to know how to take action in a meaningful way if discretionary funds and available time feel low (or non-existent) but taking, perhaps, one action each [day/week/month] might offer support in feeling more aligned with your values. Here is a very brief list of resources if you’re looking to DO SOMETHING:

American Civil Liberties Union (send messages, sign petitions)

Mobilize (a platform for finding events, petitions, and volunteer opportunities [virtually or in your state])

Mutual aid (donate dollars, supplies, or your time to our neighbors in Portland)

National Immigration Law Center (email legislators)

Portland Immigrant Rights Coalition (report ICE activity in OR, donate, print/distribute flyers)

Stand with Minnesota (a fantastic resource listing mutual aid groups/crowdfunding/ organizations lots of ways to give and take action, you can even send a “love note”)

Until next time, take good care of yourself and show up for each other as best you can.

-Laurel

[I would like to acknowledge that many immigrant families in the U.S. do not feel safe leaving their homes right now. For those of us who are able, it is a privilege to be able to leave our houses to go to work, school, or run errands without fear. As always, I encourage y’all to take what resonates from this post and leave the rest. Only you can know what feels most supportive and safe to your unique nervous system in your unique circumstances right now.]