“We don’t need to always try so hard. We can release our grip. We can release our grip on our children’s behavior and on what we think parents need to do. We can be confident that our children know better than we do about what they need to grow and learn. We can join the millions of parents around the world–and across history–who step behind the child, wait-a-bit, and let the child make their own decisions; let them make their own mistakes; and let them make their own types of kebabs. We, or an alloparent, will be standing behind them with our arms outstretched, ready to catch them if they fall.””

Recommended *with a few reservations

(7 min. read) This book was recommended by one (then two) parents in my classes before my mother also chimed in to recommend it. This well-researched book provided such a fascinating portrait of the ways multiple different Indigenous communities parent their children, as documented by NPR global health correspondent, Dr. Michaeleen Doucleff (and various other researchers). I appreciated the way Doucleff broke down the concepts outlined in the book into actionable, easy-to-implement steps. I also noticed so many echoes of Magda Gerber’s Educaring™ approach in these pages (concepts like trust, connection, and cooperation).

This book also shone light on the major bias that exists in Western psychological research–the basis for much of what we know about parenting and what children (presumably all children) need in order to thrive. This attitude of curious skepticism allowed Doucleff to discover the acronym WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic)--a term coined by three cross-cultural psychologists in 2010 to document this incredibly problematic bias. These psychologists informed us that folks from Western society, “including young children, are among the least representative populations one could find for generalizing about humans.” This knowledge led Doucleff to wonder,

“What if some of the ideas we think of as ‘universals’ when it comes to raising children are actually ‘optical illusions’ created by our culture?”

She went on to inform us that, “Much of the parenting advice out there today isn’t based on ‘scientific or medical studies,’ or even on traditional knowledge passed down from grandmas to moms for centuries. Instead, a big chunk of it comes from centuries-old pamphlets–often written by male doctors–intended for foundling hospitals, where nurses cared for dozens, even hundreds, of abandoned babies, all at once.” [I will say that not all institutional care facilities provided the same level of care. Magda Gerber based her approach largely off what she learned from Dr. Emmi Pikler’s work at the Hungarian orphanage Loczy–where children had excellent outcomes compared to other children growing up in residential nurseries.]

This knowledge alone allows us to be more discerning consumers of parenting advice.

A few things I loved about the book:

The way Doucleff provides us with such an honest portrait of the struggles she encounters on her parenthood journey

Concrete suggestions for ways to step back and move away from entertaining and micromanaging your child’s life and experiences

A focus on a holistic, balanced approach to family life

choosing activities the entire family–including parents–will like, instead of focusing on child-centric activities

do chores together with your child (not during naps or in the evening)

Highlighting the value of play and storytelling to solve problems

A belief in children’s inherent goodness and their capacity for kindness, cooperation, and empathy

An emphasis on providing children with meaningful work and real tools (this nurtures their growing capacity to be of real help in successfully–and willingly–assisting with the day-to-day tasks of their family)

Prioritizing strategies for honing our own self-regulation skills

Doucleff describes an illuminating conversation she has with Maria de los Angeles Tun Burgos, a mother of three, who lives in a Maya village on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico:

“No matter what I do, Alexa wants to do it, too,” Maria says. “When I’m making tortillas, Alexa starts crying if I don’t let her make tortillas. And afterward, she always wants the broom to sweep up.”

“And she actually sweeps and is helpful?”

“It doesn’t matter. She wants to help somehow and so I permit her,” she says…

“Whenever she wants to help, you let her?” I ask, still not understanding. “Even if it makes a giant mess?”

“Yes. That is the way to teach children.”

Photo by Fausto Hernández via Pexels

Helpfulness can indeed be squelched when parents and caregivers consistently forbid or divert/distract children away from attempting new, challenging tasks because we’re worried about mess or efficiency and/or lack the ability to regulate ourselves enough to step back and allow children opportunities to flex their “me do it” muscles.

While I loved so many of the ideas in this book, I disagree with a few of Doucleff’s suggestions:

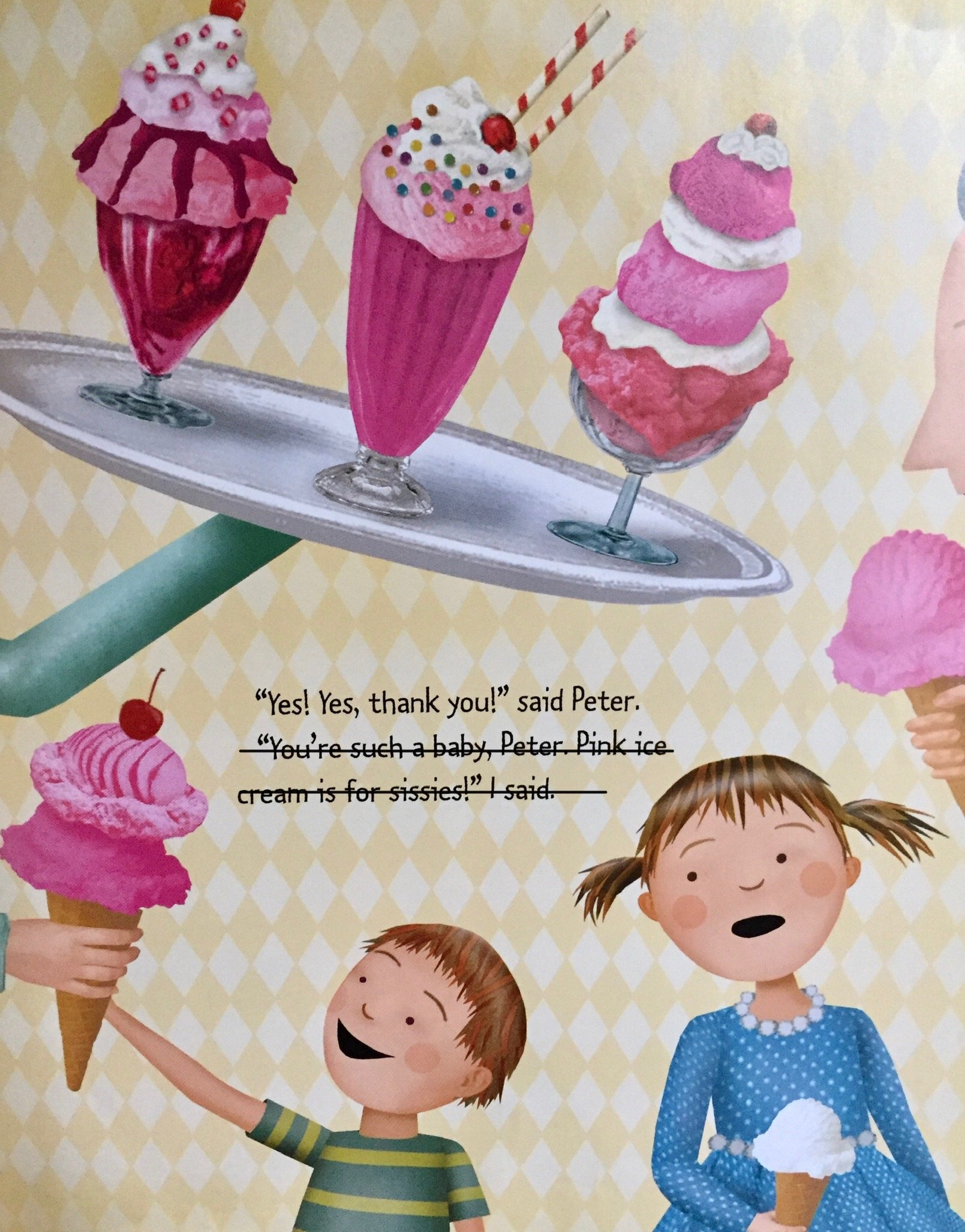

Using “big girl” vs. “baby” as a way to motivate behavior '

“If she doesn’t clean up her toys or help with this dishes, I say, ‘Oh, you didn’t do it because you’re a baby?’”

“If I hear a lot of whining and demanding on grocery day, I might ask, ‘Do whiny babies get to go to Trader Joe’s?’”

While Doucleff doesn’t suggest doing this sarcastically or mockingly necessarily, it still doesn’t feel right to take advantage of a child’s strong desire to feel mature and like a “big kid,” even if it’s “effective” in the short term.

Photo by Jen Theodore on Unsplash

The use of frightening “stories” to gain compliance

E.g. Monsters will come if you leave the fridge open, spiders will grow in your dress because you won’t take it off to be washed

This is a perfect example how it can be problematic to take a strategy out of the original context and try to apply it in a different circumstance. (Doucleff describes how Inuit families use such stories to keep children at a safe distance from the icy ocean–a strategy that is important in their community to protect children. Using the same strategy to save a little bit of electricity or launder a dress seems problematic and completely unrelated to safety.)

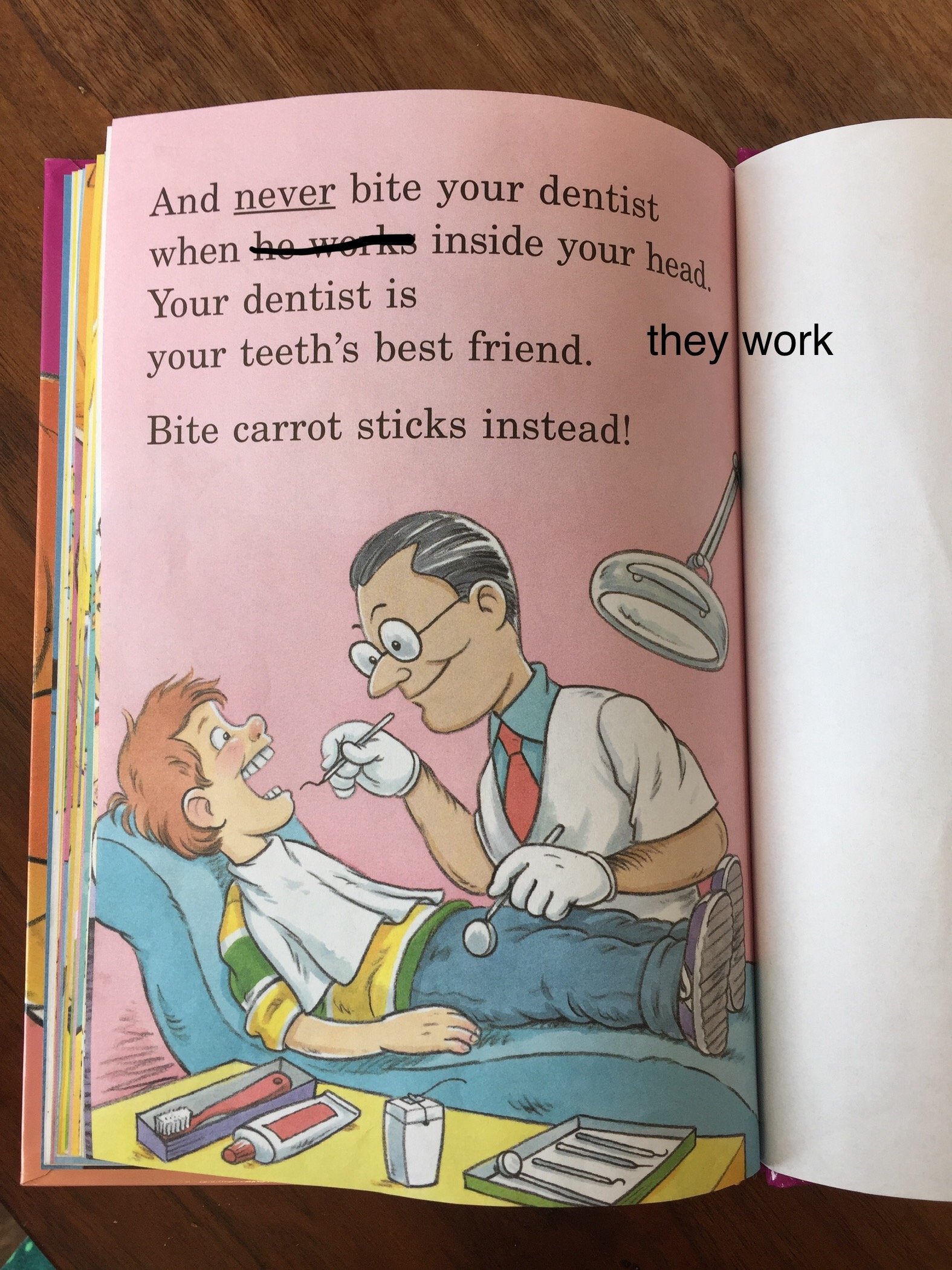

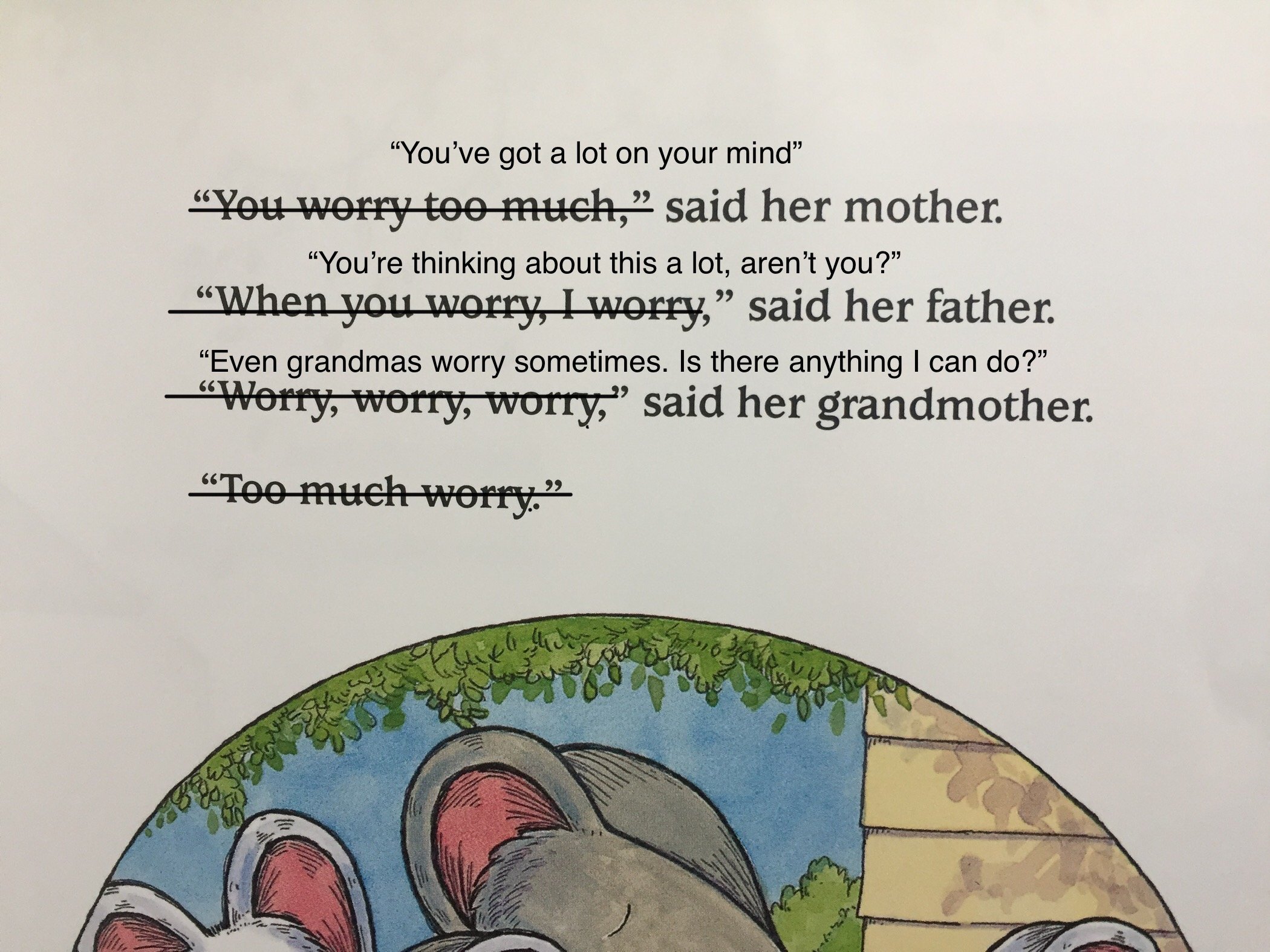

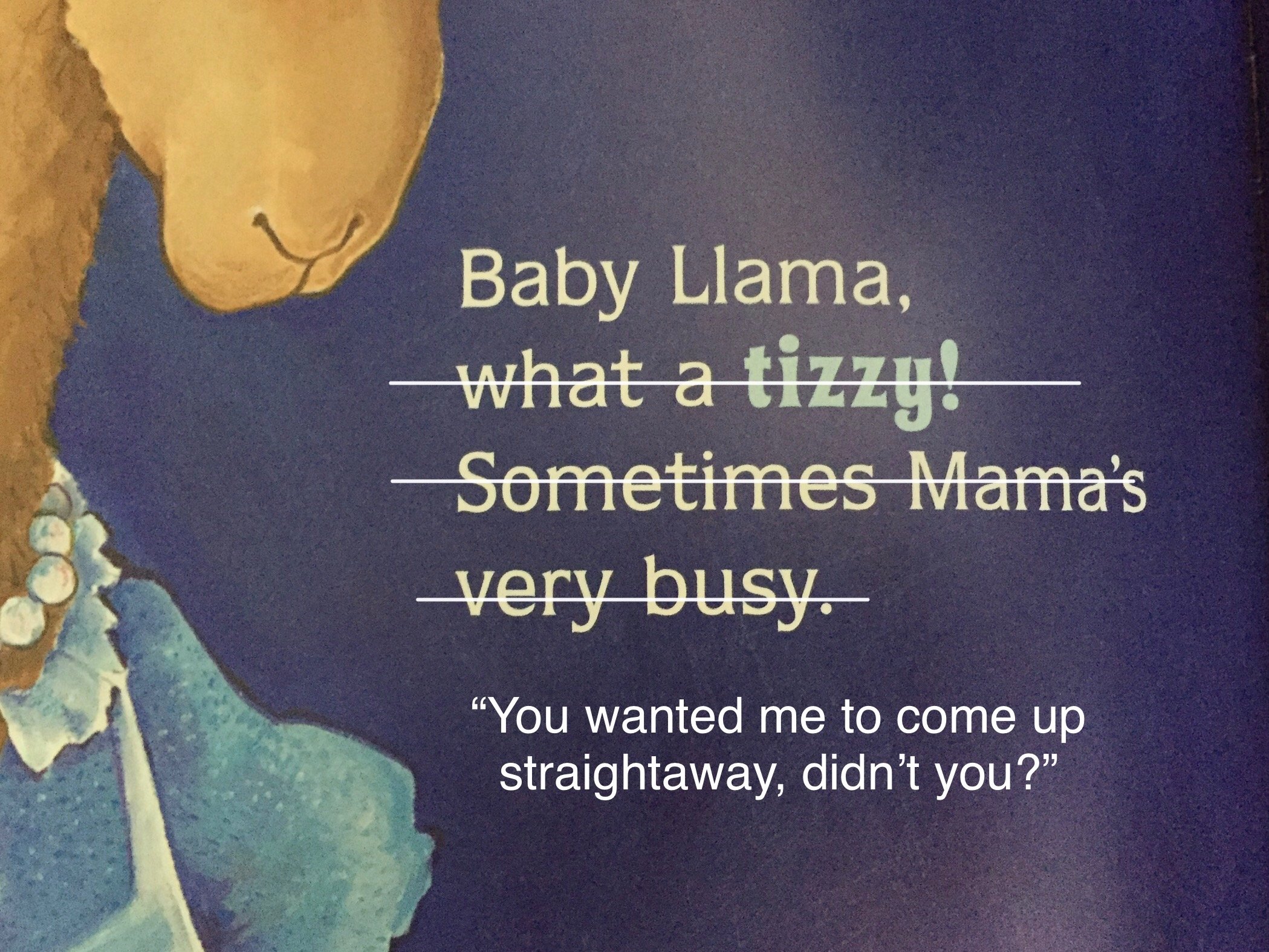

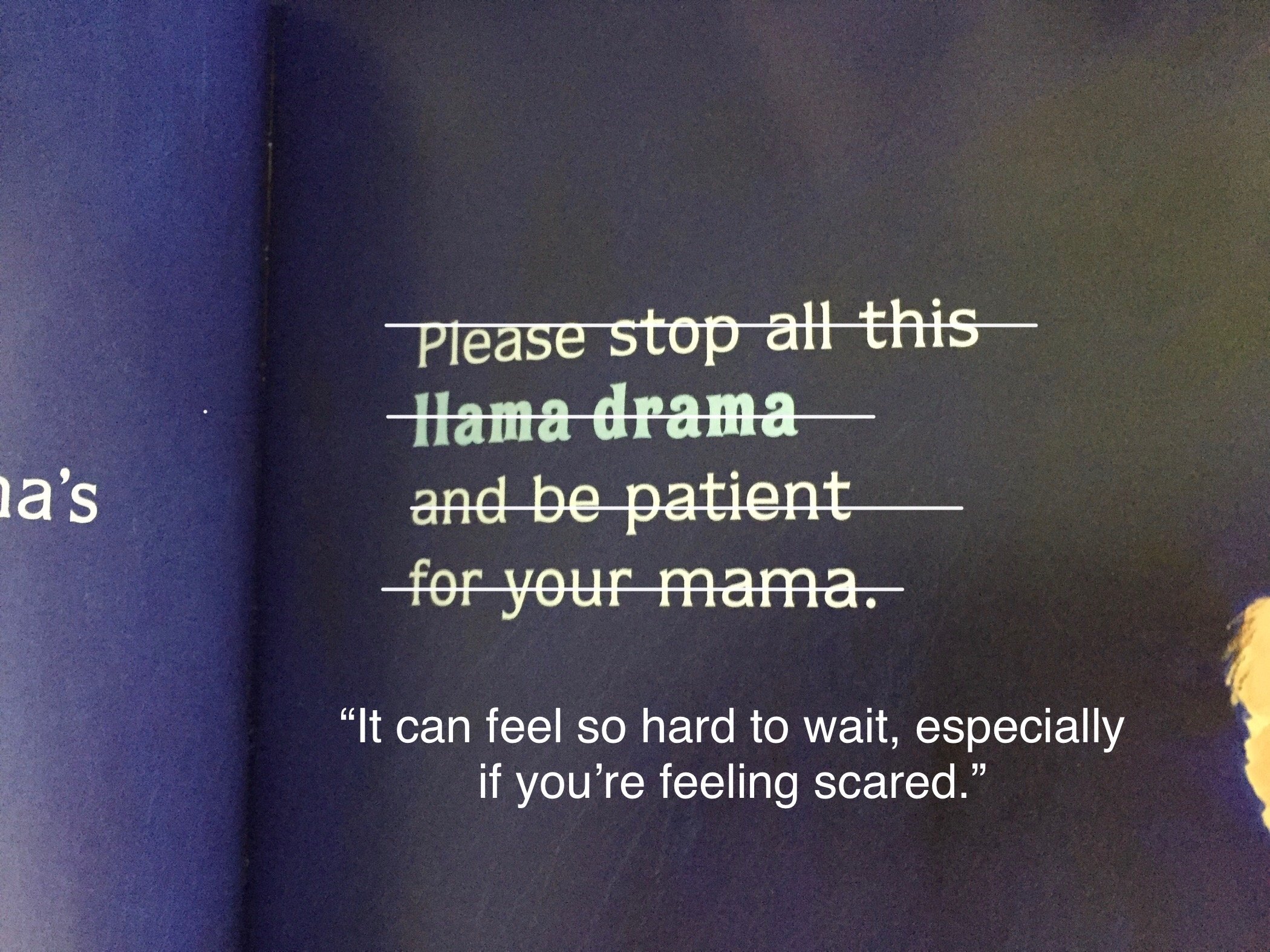

Ignoring children’s inappropriate behavior

“Ignoring children makes a powerful tool for disciplining”

“Learn the art of ignoring… pretend like you can’t even hear or see them. With this flat expression, look into the horizon above the child’s head or to their side.”

“Parents can teach children which emotions aren’t valued in the home by not responding to those emotions.”

Alfie Kohn summarizes a fascinating finding directly related to this type of conditional parenting: “An important new metaanalysis of 31 studies (with >11K participants) on the subject of conditional parenting - either doling out or withholding affection/approval to elicit certain behaviors - confirms a range of negative effects from both versions. Effects of these manipulative parenting tactics (positive reinforcement, deliberate ignoring, etc.): feelings of contingent self-worth, a diminished sense of autonomy (as kids act less out of choice than to quell guilt or anxiety), depression, and impaired parent-child relationships.”

A few other ideas I’m less concerned about but that gave me pause:

The language of “training” children (“steps to training a child”)

A child is not a dog. We can guide children, coach and support them, we can model values and behaviors that are important to us but we can’t train them.

While I recognize that this might seem like an insignificant gripe, I think the language we use is important. [How would you feel if your partner was reading a book with a section titled, “Steps to training a husband/wife/partner?”]

Threatening to throw away a child’s toys if they don’t clean up

“Last chance to clean this up or it’s going in the trash!”

I agree that children often have more toys than they can manage themselves (not their fault) but I think there are more respectful ways of reaching an orderly space (that don’t require threats).

As always, I think it’s crucial to read parenting books with a critical eye (especially those written by folks outside of the child development/developmental psychology field), and this book is no exception. I think the underlying premise of this book–that great wisdom is held in Indigenous communities worldwide and we have a lot to learn from them–is incredibly valuable and I loved diving into accessible, engaging, thought-provoking research. However, the author also makes some suggestions that go against what most psychologists and child development experts agree to be best practice (her degrees are in chemistry, viticulture [the cultivation of grapevines], enology [the study of wines] and biology).

Take what you like and leave the rest.

The Multnomah County Library has 20 copies of this book and currently only a few holds.

Haines, J. E., & Schutte, N. S. (2022). Parental conditional regard: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12111

Kohn, Alfie. Parental Love with Strings Attached. (2009).

Onion, R. (2021, March 6). There is no Parenting Utopia. Slate. https://slate.com/human-interest/2021/03/hunt-gather-parent-book-review.html