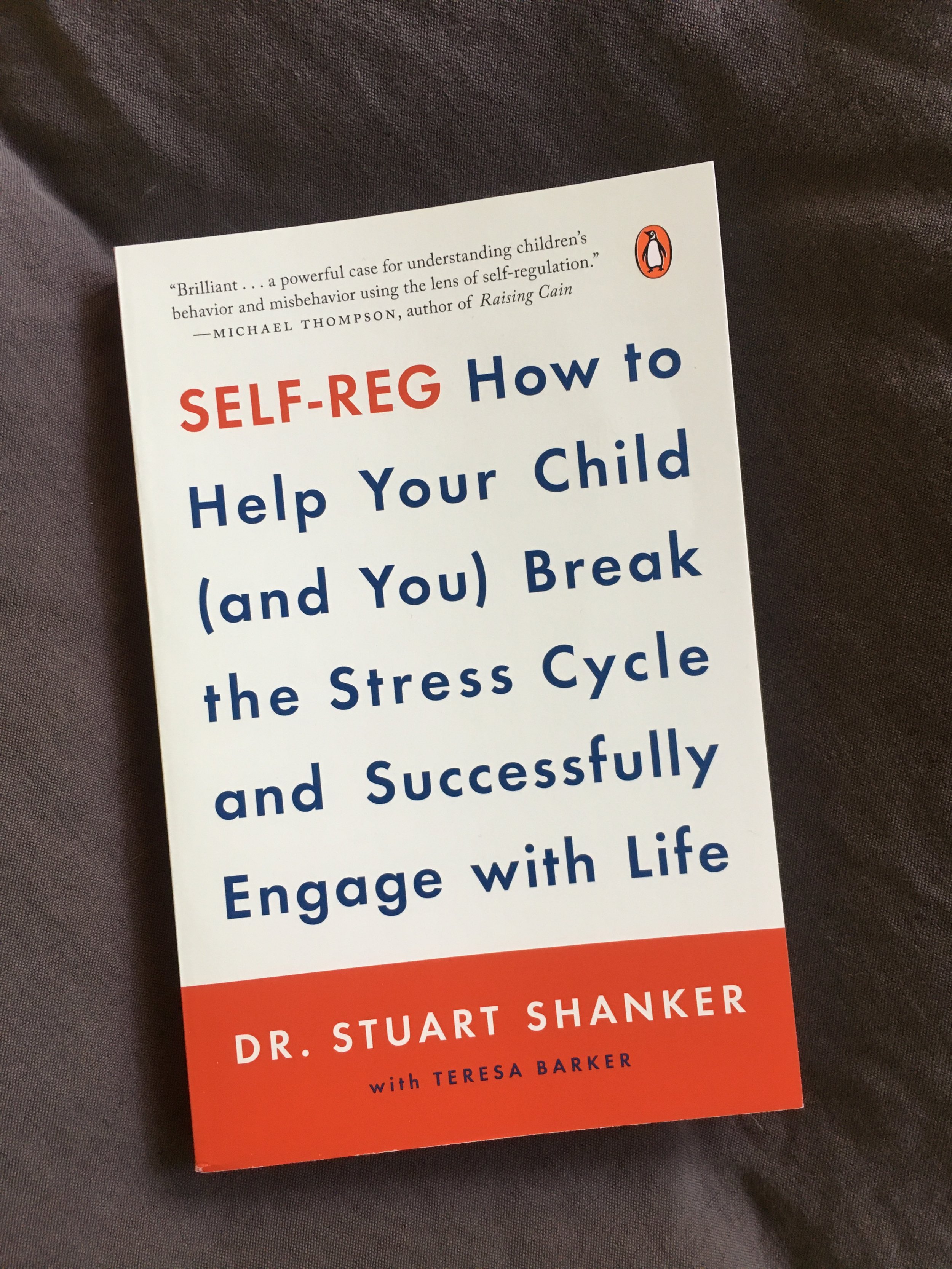

In May, after 12 weeks of coursework, I completed the Self-Reg in Early Childhood Development Certificate Program through The MEHRIT Centre. I had devoured Dr. Stuart Shanker’s book Self-Reg: How to Help Your Child (and You) Break the Stress Cycle and Successfully Engage with Life a few years ago and was fascinated by the accessible way Dr. Shanker had synthesized interpersonal neurobiology and elements of Polyvagal Theory in this highly practical and intuitive guide.

Recognizing that stress was the common denominator impacting both overwhelmed parents and dysregulated children (and each and every one of us living on the planet today), I decided that studying Self-Reg in greater depth would support my work with both parents and early childhood educators.

Self-Reg is a process, developed by Dr. Stuart Shanker, for supporting humans of all ages with navigating the stressors they encounter throughout the course of their lives. Our ability to function optimally in our work, our passions, and our relationships–with flexibility, engagement, and curiosity–requires that we are continually evaluating our energy and tension levels and finding ways to bring ourselves (and the children we care for) back into balance.

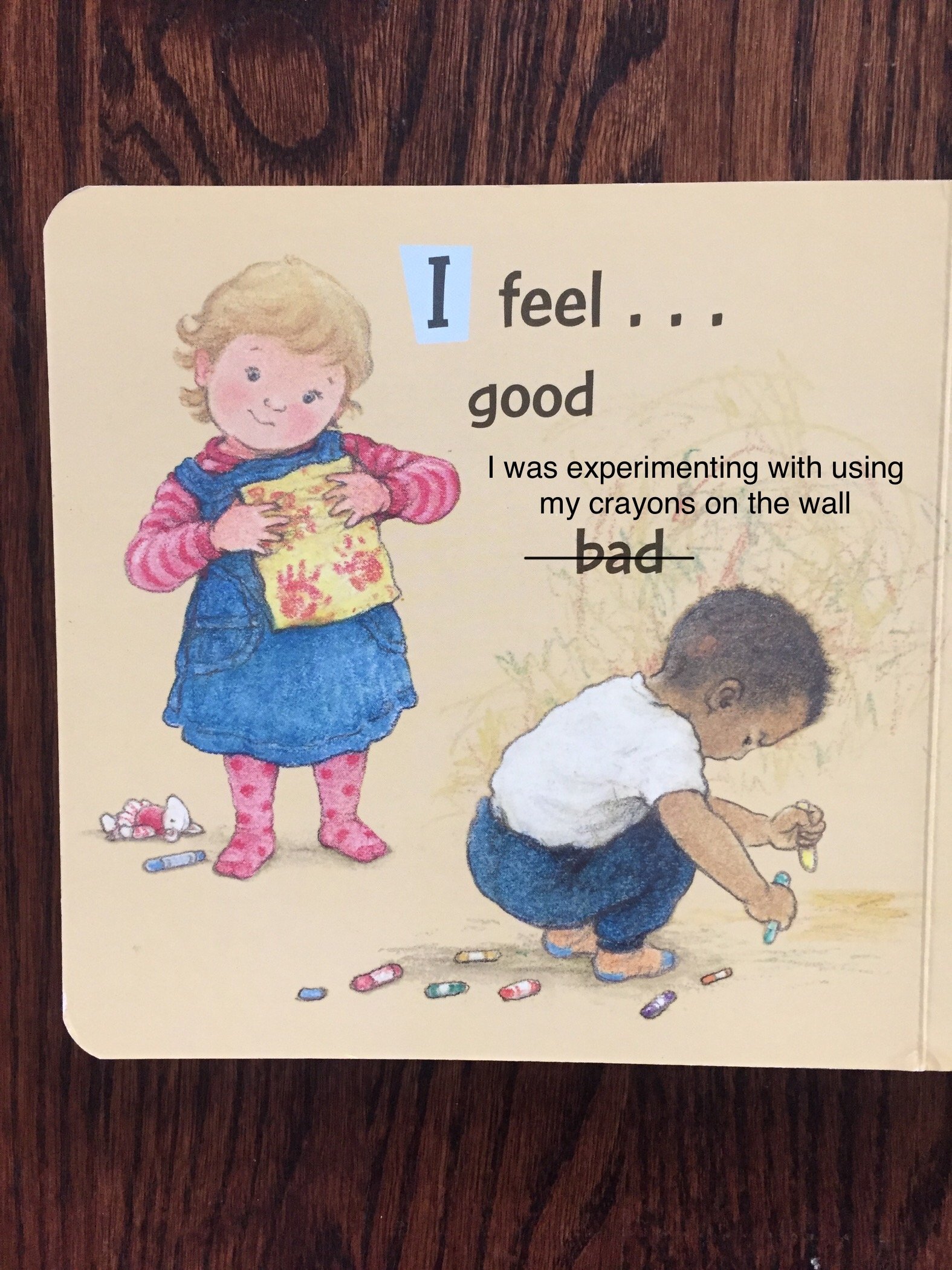

When our energy dips and our tension rises (think: your commute home after a long day at work), we become vulnerable to any number of reactions (e.g. road rage, stress eating) that might not be aligned with our core values. Traditionally, our society tells us that a lack of control or ability to follow through is a personal, moral failing, and that we just need to “try harder.” As Dr. Shanker reminds us, “Self-control is about inhibiting impulses; self-regulation is about identifying the causes and reducing the intensity of impulses and, when necessary, having the energy to resist” (Shanker, 2016, p. 6). Well that’s a more compassionate and effective way of working with impulses, now isn’t it?

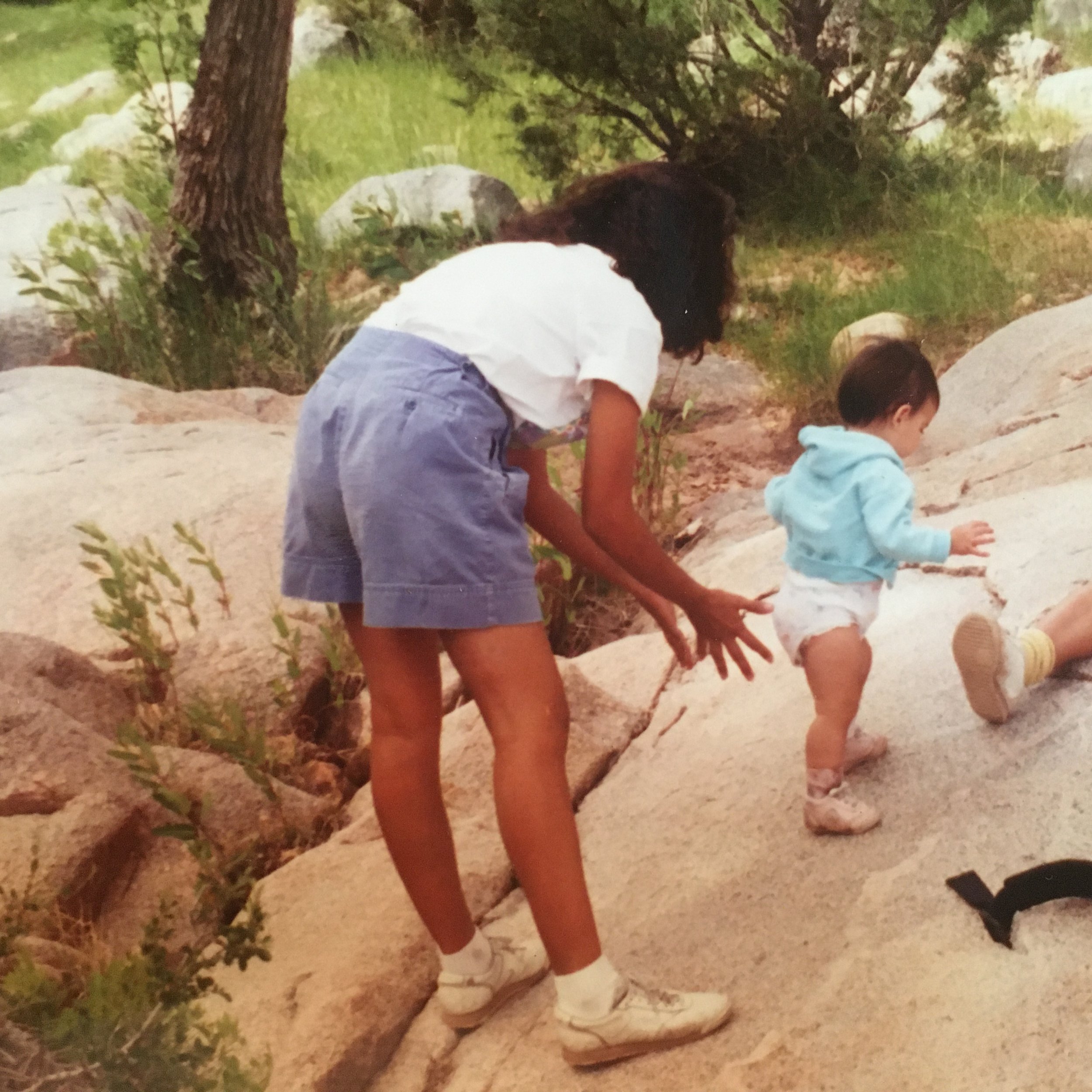

We all experience stress in different ways and have different needs to maintain optimal energy and tension levels. Infants and young children have immature capacities for self-regulation and rely heavily upon their caregivers to support them in returning to a state of balance. Children's nervous systems are incredibly flexible from birth to approximately age eight and, because of this, this is the time our support and coregulation can make the most difference, supporting all domains of learning and development.

One of the five steps of the Self-Reg process (I’ll speak to the other steps in an upcoming post) is to identify stressors, both in yourself and your child. Stressors refer simply to “anything that disrupts homeostasis” and depletes our energy stores (Shanker, p. 97). Once you become a “stress detective,” as Dr. Shanker calls it, you’ll notice that stressors are everywhere! Another fascinating element is that each of the domains are inextricably connected to each other. Stress in one domain can increase stress reactivity in the other domains. This is why something as unassuming as the low-grade hum of household appliances (to a sound-sensitive person) can reduce your capacity for remaining calm during your child’s next tantrum.

There are five domains of stress: biological, cognitive, emotional, social, and pro-social. I’ve included just a few examples of each stressor but there are many more examples of each.

Biological stressors refer to anything that causes or contributes to physical discomfort in your body. Examples include: pain, allergies, illness, fluorescent lighting, loud or persistent/repetitive sounds (gas leaf blowers, anyone?), uncomfortable clothing, insufficient sleep/rest, scented products, motor/sensorimotor challenges, trying to sit still when your body wants to move, and visual clutter.

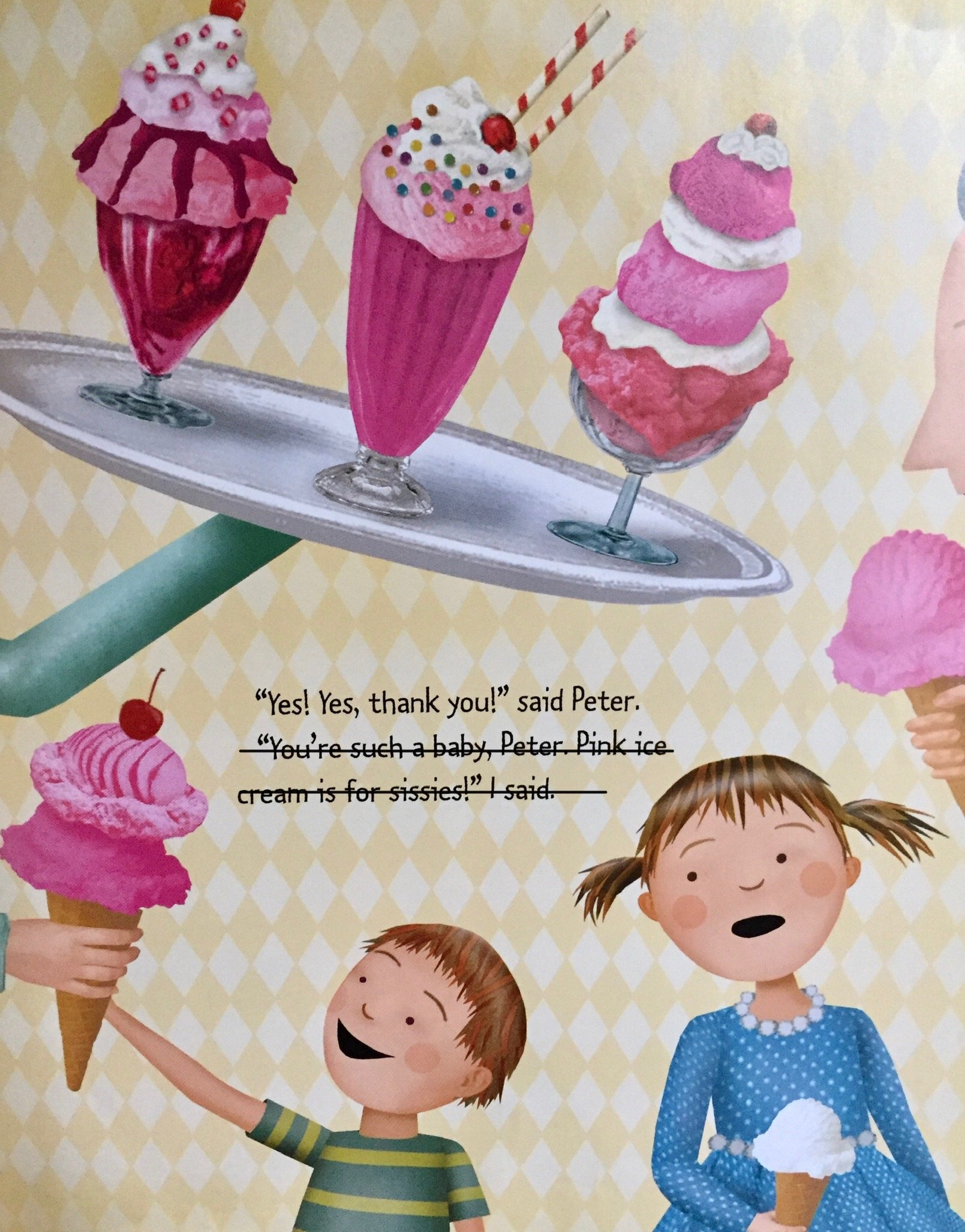

Cognitive stressors include multitasking, competition, being interrupted, learning something new (e.g. a new language), expectations that are inappropriate for a child’s age/stage, challenges with working memory, time pressure, making decisions, and a slower processing speed.

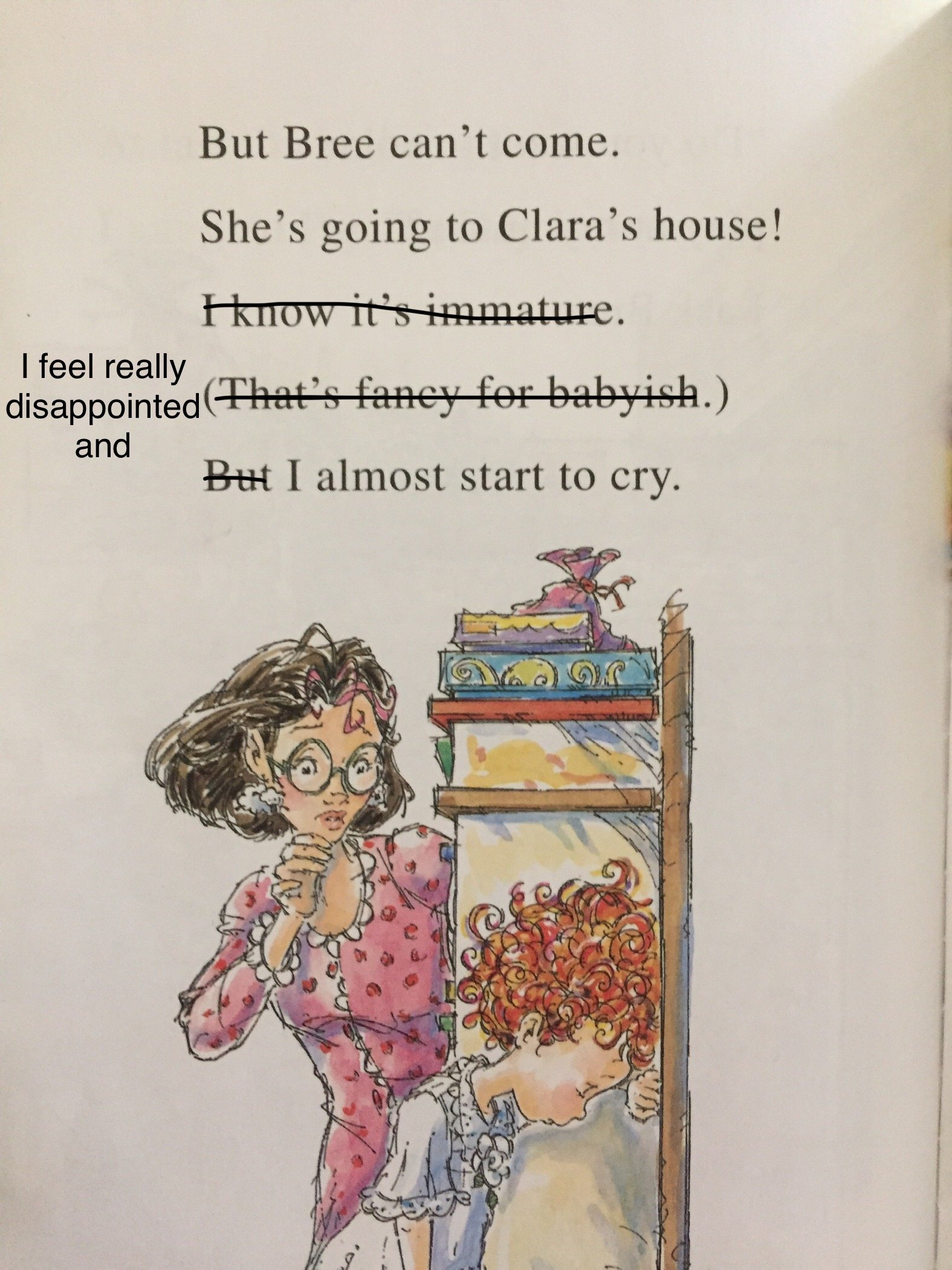

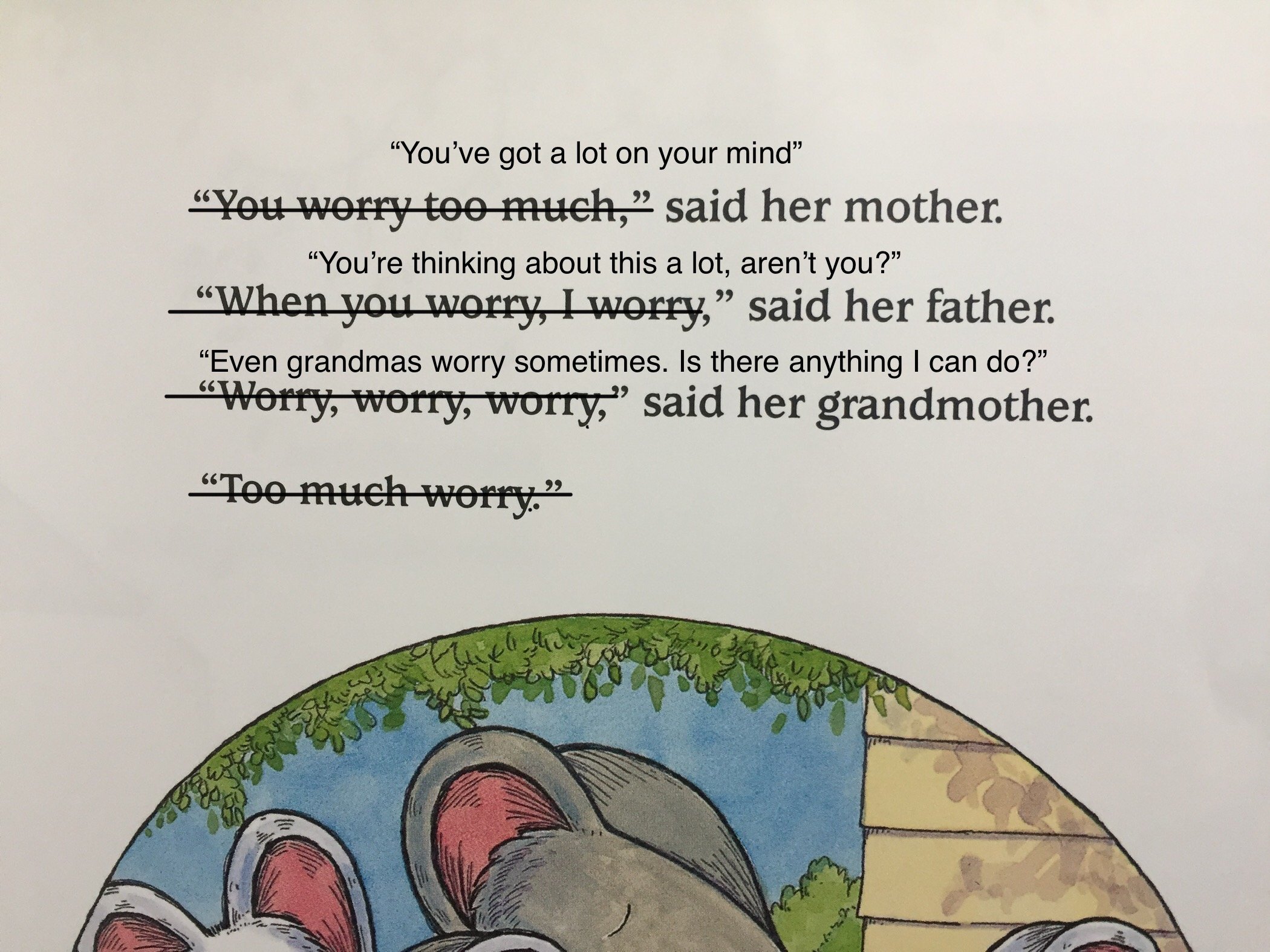

Emotional stressors include all of those feelings that can impact us such as embarrassment, frustration, rage, fear and worry, helplessness, and events that trigger these emotions, like saying goodbye to a parent at school or anniversaries of grief, loss, or trauma. And remember that even “positive” emotions like excitement, or surprises (have you seen Kristin Bell's sloth meltdown?), holidays, and birthdays, can all contribute to disequilibrium.

Social stressors “relate to a child’s difficulty picking up on social cues, and understanding the effect of their own behavior on others” and include difficulty interpreting or hypersensitivity to nonverbal cues, challenges anticipating the behaviors of others, being left out/feeling rejected, disagreements/interpersonal conflict, large groups, a new school/class/teacher, SIBLINGS, and neurodivergent masking.

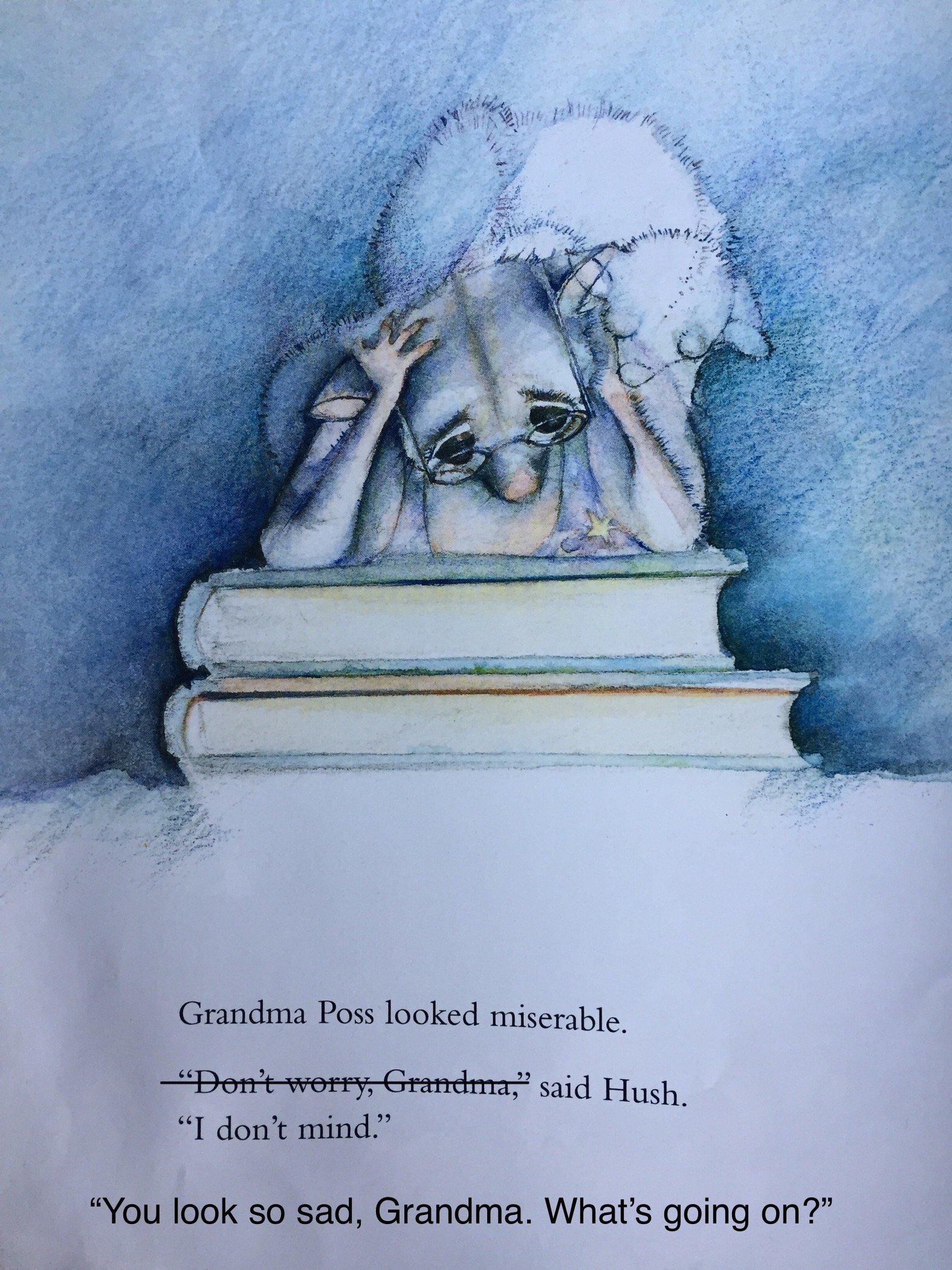

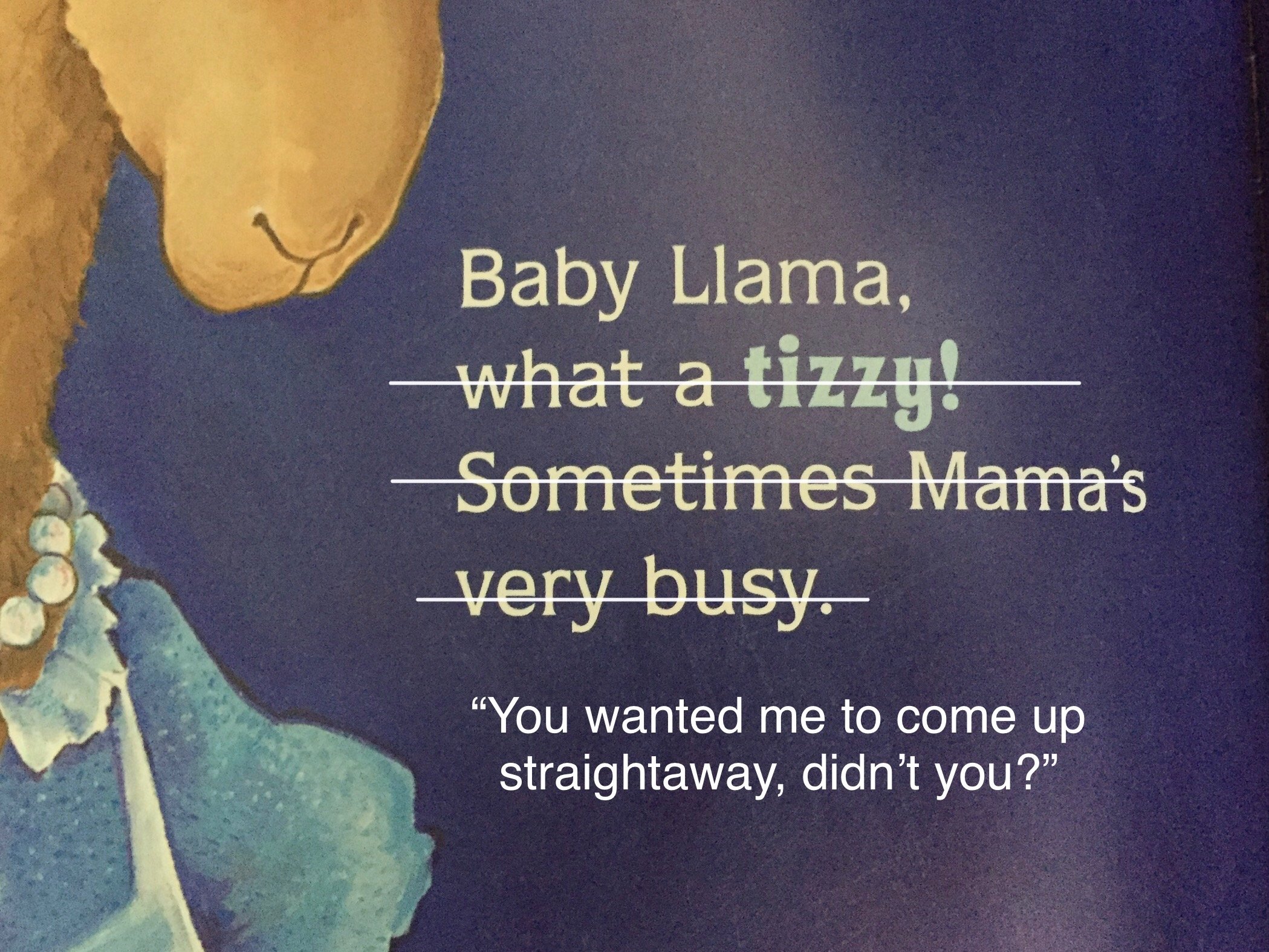

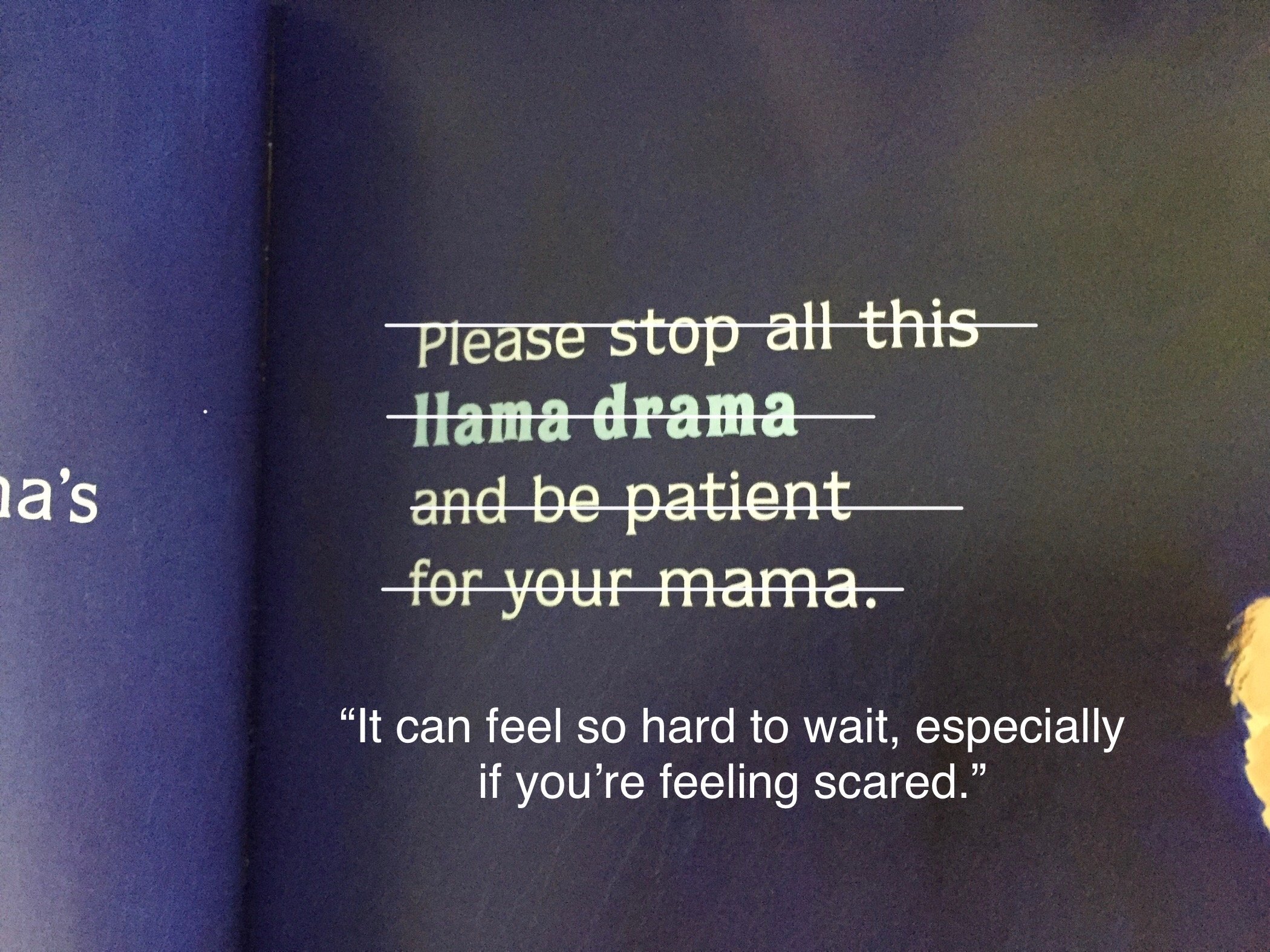

Prosocial stressors refer to the experience of “Being exposed to someone else’s stress or being expected to put someone’s needs ahead of your own” (Shanker, p. 193).

For adults this might look like the experience of having a child/partner/family member/friend who is sick, being late, disregarding your own needs to meet the needs of another (I see you, parents!), riding the emotional roller coaster alongside your child, walking by an unhoused person sleeping on the ground, feeling unable to summon empathy due to burnout or compassion fatigue, feeling responsible for the safety of others, and being unable to alleviate the suffering of others.

For children this might look like feeling or sensing your parent or caregiver’s stress, having acted impulsively towards the baby (and now the baby is crying and your parents are upset with you), another child playing with your toys in your space, being asked or expected to be understanding/accomodating because you’re older, a child crying in your classroom, and having to wait while your parent feeds the baby. Perhaps you exhibit some behavior (e.g. telling your parent that you hate them) that is completely developmentally appropriate but this ends up triggering something unresolved in your parent and they take it personally. Your role is now to set your needs aside and comfort them. Knowing you have the power to completely derail your parent can be a terrifying experience for a child.

As we’re thinking about stressors, keep in mind that there are multiple types of stress:

obvious/overt vs. hidden

minor/tolerable vs. traumatic/toxic

and

negative (distress) vs. positive (eustress)

The goal is not to eliminate stress entirely (otherwise we would not grow as humans as all growth requires some amount of discomfort) but rather to become acutely aware of your own triggers (and your child’s) and eliminate unnecessary / reduce excess stress when you can.

Now that you’re thinking of stressors, you may have the urge to begin tracking your child’s stressors straightaway… of course you do! However, I encourage you to begin by tracking your own stressors for the next week or so before diving into your child’s stressors. As you’re tracking, remember that it’s not too important to accurately label which domain a stressor is in (many, like birthday parties, encompass all domains…woohoo!). As Dr. Shanker reminds us, “Self-Reg starts with how well we can identify and reduce our own stressors and how well we can stay calm and attentive when we’re interacting with a child” (Shanker, p. 7).

Self-Reg is one of the most powerful approaches I’ve found that can help make sense of children’s challenging behaviors and determine what they actually need to “successfully engage with life.” I look forward to exploring it more alongside you!

Stay tuned for part 2 :)

Take good care,

Laurel

If you’re interested in learning more about Self-Reg and Dr. Shanker’s work, check out The MEHRIT Centre. In addition to their awesome blog and podcast, they also offer a free Intro to Self-Reg webinar for parents and also an affordable, self-paced learning option, the Self-Reg Parenting Course.

References:

Example Stressors in the 5 Domains of Self-Reg

Shanker, S. (2015). Self-Reg: How to Help Your Child (and You) Break the Stress Cycle and Successfully Engage with Life. Penguin Books.